COVID-19 from the margins

As the COVID19 pandemic spreads around the world, a range of surveillance techniques have been implemented widely to combat the virus and the tremendous new challenges it poses for all. Indeed, fighting a pandemic is considered a legitimate aim of surveillance under international law. But how to make sure that the surveillance targets the disease, or the virus, and not the people who may or may not be carrying it?

The question is important, as communities at the margins are often impacted disproportionately by surveillance: when it doesn't take inequalities into account, surveillance tends to reproduce, and even deepen, their marginalisation, rather than leading to an improvement in their lives - even during a pandemic.

Through research and other initiatives, we have therefore attempted to understand how to ensure the interests of these communities are fully taken into account in any surveillance measures to battle the pandemic, and have made a range of recommendations accordingly.

Understanding bodies, data and embodied experiences of surveillance and control during COVID-19 in India

By Radhika Radhakrishan

Disembodied constructions of data as a resource erase connections between data and people’s bodies and make surveillance seem innocuous. In contrast, this research study adopts a feminist bodies-as-data approach, to pinpoint the specific, embodied harms of surveillance during COVID-19 in India. Starting from lived experiences of marginalised communities whose voices are often left out in debates on data protection, it shows that surveillance undermines not just data privacy, but more importantly, the bodily integrity, autonomy, and dignity of individuals.

Profiling India’s emergent ecosystem of networked technologies to tackle Covid-19

By Chithira Vijayakumar and Tanisha Ranjit

How useful have apps, drones, online portals, and the National Migrant Information System been to tackle Covid-19 from a public health perspective? To what extent have they impacted social control? And how have marginalised people been affected in particular? This research study maps the deployment of these technologies and the evidence available so far of their usefulness to tackle the crisis.

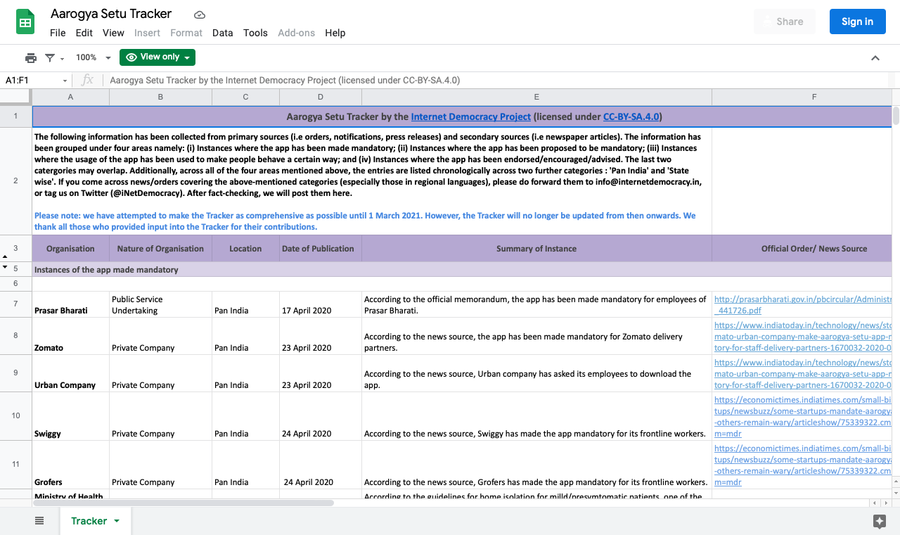

Tracing the imposition of Aarogya Sethu, India’s contact tracing app

Aarogya Setu tracker — by Tanisha Ranjit

-

When and where is Aarogya Setu mandatory? We’re keeping track

The Indian Government has launched the Aarogya Setu app as a response to COVID-19. While initially termed voluntary, we noticed that soon after its launch, the app started to be pushed by various governments, non-government establishments and private bodies as mandatory, or forced on people in other ways. Our Aarogya Setu Tracker attempts to document all these cases. Access the Aarogya Setu Tracker here. To make the tracker as exhaustive as possible, we need your help! If you come across relevant news items/orders (especially those in regional languages), please forward them to info@internetdemocracy.in or tag us on Twitter (@iNetDemocracy). After fact-checking the item, we will add it to the tracker. More

-

‘Best effort basis’: Is it indeed the best effort by the Government?

The Government issued an order on 17 May 2020 that appeared to dilute the ‘mandatory’ nature of the Aarogya Setu app. According to this order issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs, employers on ‘best efforts’ are asked to ensure the downloading of the app. Additionally, District Authorities may also ‘advise’ individuals to download the app. This was a refreshing move as previously issued guidelines on the lockdown had made the app mandatory for both private and public employees as well as those in containment zones. At first sight, there seems to be a reason to celebrate. But is this the case in practice? More

-

An anniversary we are wary about

On 2 April 2020, the Government of India launched the Aarogya Setu app with the stated intention of curbing the pandemic — and a lot has happened with it since. Post its launch, the app was heavily promoted and made mandatory by different public and private entities for various purposes. The prescription of a state-sponsored app raises many concerns. In addition to the issue of data privacy and security, such an imposition can lead to an infringement of fundamental rights. It can exclude those who do not have access to a mobile phone. More

-

Aarogya Setu: Mandatory or not? We traced it for eleven months through our Tracker

We traced whether Aarogya Setu was mandatory or not during the last 11 months from 8 May 2020 to 1 March 2021. The government claimed it wasn’t, but practice seemed to play out differently. Here is what we found. More

In short

-

How Covid-19 helped government control your data and you

Pandemic-era data-enabled surveillance — via digital tracking, disinformation, a variety of apps, phones and drones — undermines data privacy, autonomy and dignity of individuals and specifically disadvantages women, research shows.This piece was first published in Article 14. More

-

Embodied surveillance during COVID-19 in India: A feminist perspective

Guidelines on public mobility may be needed to control community transmission. However, when this is carried out in a manner that evokes fear without taking into account the socio-economic contexts and needs of people, then it is not the disease being controlled, but rather the bodies of people through threats of collecting their data. This article was originally published for Observer Research Foundation (ORF) CyFy Edit here. More

-

At stake is our bodily integrity

Governments around the world are increasingly turning to technology as a tool to combat the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. In India, these tools have ranged from various contact tracing apps to using drones. Privacy concerns have been raised about the use of such intrusive digital technologies by activists, lawyers and concerned citizens. But while these are valid, a crucial element remains unrecognised: what is at stake is not merely our informational privacy, but our autonomy, dignity, bodily integrity, and equality. Note: A shorter version of this article was originally published in the Hindu. More

-

An exclusion tale: Aarogya Setu’s march from optional to mandatory

As Aarogya Setu is becoming mandatory in a growing number of cases, it deserves to be asked: does the app ensure welfare for all – or not at all? In this column, we try to answer that question. We look in particular at the implications that the mandates pose on people’s lives and fundamental rights, especially on marginalised sections of the community. We also highlight the other concerns with the app: the issues of efficacy, potential tool for mass surveillance and exclusionary nature of the app. This opinion piece was originally published in The Quint, on 6 May 2020. More