Virus detected: A profile of India’s emergent ecosystem of networked technologies to tackle Covid-19

A report by

Chithira Vijayakumar & Tanisha Ranjit

in

Data

Abstract

How useful have apps, drones, online portals, and the National Migrant

Information System been to tackle Covid-19 from a public health

perspective? To what extent have they impacted social control? And how

have marginalised people been affected in particular? This research

study maps the deployment of these technologies and the evidence available so far of their usefulness to tackle the crisis.

The study was conducted as part of the Covid App project.

The Covid App project is a civil society initiative that stemmed from a research interest in Covid-specific interventions – especially contact tracing apps – in countries outside Europe and North America. This shared research focus drew together six civil society organisations: ALT Advisory (South Africa), Internet Democracy Project (India), InternetLAB (Brazil), Karisma (Colombia), SMEX (Lebanon), and United for Iran. AWO, a data rights agency, provided coordination support.

Over a 7-month period, the group reviewed contact tracing apps and assessed their interaction with public health, human rights, privacy, and data protection in the six countries of focus. We conducted interviews, filed freedom of information requests, and extensively reviewed public documentation to produce in-depth country reports. Contact tracing apps cannot be evaluated in a vacuum: the research considers alternative measures, technological and others, that were deployed in response to the pandemic, and often interacted with the design and deployment of contact tracing apps themselves.

Today, we publish the in-depth country reports – each accompanied by a set of recommendations – alongside an expert technical review of seven contact tracing apps from our countries of focus.

We hope our contribution will support the critical evaluation of contact tracing apps and other pandemic measures. In addition, we hope to foster a discussion of safeguards – including recourse and oversight – that will better protect marginalised and vulnerable groups during public health crises, bolster human rights, democracy, and rule of law, and strengthen future pandemic response.

INTRODUCTION #

If 2020 goes down in history as the year of Covid-19, it was also, undoubtedly, the year of digital technologies. One by one, as countries all over the world closed their borders and shuttered their businesses in the span of a few short weeks, people turned to technology as their primary communicative arena, and nation states turned to it to conduct epidemiological surveillance and monitor lockdown enforcement. Homes turned into offices, as jobs and services that could be shifted online did so, including government services, education, financial transactions, medical care and more. The volume of information, both personal and otherwise, that was being collected, stored and shared through the digital scaffolding of the internet skyrocketed.

This was true of India as well, where 688 million internet users put the country second on the global leaderboard of internet users. And yet, more than half the population of the country still lacks access to the internet. Notably, the Indian government’s 2018 Survey on Household Social Consumption: Education had found that even amongst those who could access the internet, only about 20% knew how to use it.12 The digital divide in the country is vast, in terms of access as well as knowledge.

Data protection rights in India currently exist in a peculiar legal limbo: in August 2017, the Supreme Court of India deemed privacy to be a fundamental right, stemming from the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution. The Court had also noted that privacy of personal data is a critical aspect of the right to privacy. Subsequently, the 2019 Personal Data Protection Bill was introduced by the Minister of Electronics and Information Technology in Parliament. The bill was referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee for review, where it currently remains.

An enormous ecosystem of apps and technological tools have taken root and flourished in the country, particularly for managing the Covid-19 pandemic. Without question, accurate data are indispensable for managing a public health emergency such as Covid-19, and harnessing technological and data-driven innovations can enable governments and healthcare workers to make more informed decisions. But in the absence of any formal legal regulation, many of these tools are subject to self-regulation, as this report details.

Covid-19 in India

On January 30, 2020, the first case of Covid-19 in India was confirmed in the State of Kerala.3 The seriousness of the emergent situation was clear, as three days later the death toll in China due to Covid-19 exceeded that of the 2002-03 SARS outbreak.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) designated the Indian Institute of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National Institute of Virology (NIV) to research and develop methodologies to tackle Covid-19. This is a notable departure from the government’s established strategy, since the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP), a government initiative under the Health Ministry’s National Centre for Disease Control launched in November 2004, was absent from the strategizing and monitoring of the pandemic.4 IDSP was created a year after the SARS outbreak with the explicit mandate of tracking diseases and pandemics. It has well-established surveillance units at the central, state and district levels that track the outbreak of diseases. These data are then compiled into detailed weekly reports, which are published on their website.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the nation regarding the pandemic for the first time on March 3, 2020, through a tweet.5 He stressed that there was “no need to panic”, and that “Different ministries & states are working together, from screening people arriving in India to providing prompt medical attention.”

On March 12, 2020, one day after the WHO officially declared Covid-19 a pandemic, India reported its first death from the virus, in Kalburgi, Karnataka.6 The government banned the entry of foreigners and suspended all visas for travel to India for a month. The next day, Health Ministry Joint Secretary Lav Agarwal spoke to reporters at a press conference and said that Covid-19 is not a health emergency, and that there was no need to panic. He also stated that 42,000 people in the country were under community surveillance.7

On March 22, Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared a “Janata [Public] Curfew”, a 14-hour lockdown from 7 am to 9 pm on a Sunday. He added: “Our experience of Janata Curfew will help us chart the way ahead for tackling coronavirus in India.” Anyone who was not associated with essential services, such as health, government services, sanitation and the media, was directed to stay indoors. The Prime Minister also said that in order to show the nation’s appreciation for the frontline workers who were battling Covid-19, all citizens should come out onto their balconies or yards at 5 pm, and clap or ring bells for five minutes.8 India had reported a total of 360 cases and tested a total of 16,021 individuals up to the Janata Curfew.

At 8 pm on March 24, 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi ordered a nationwide lockdown for 21 days, starting at midnight.9 At this point, the total number of positive cases in the country was 606. The world’s largest lockdown, for 1.3 billion people, was mandated with four hours’ notice. All international and domestic flights, all forms of public transportation, and all inter-state and intrastate travel were halted overnight. On April 14, India extended its nationwide lockdown till May 3, which was followed by two-week extensions starting May 3 and 17, with progressive relaxations in restrictions.

On March 29, 2020, the Union Home Ministry had issued an order under the Disaster Management Act to set up 11 Empowered Groups of Officers to deal with the various challenges the pandemic had created. The order, signed by the Union Home Secretary Ajay Bhalla, as Chairman of the National Executive Committee, stressed the need to synchronize efforts across ministries and departments. The Empowered Groups were for (i) planning for medical emergency; (ii) establishing the availability of hospitals, isolation and quarantine facilities, disease surveillance and testing; (iii) ensuring availability of essential medical equipment; (iv) augmenting human resource and capacity building; (v) managing supply chain and logistics; (vi) coordinating with private sector; (vii) instituting economic and welfare measures; (viii) providing information, communications and public awareness; (ix) managing technology and data; (x) channeling public grievances; and (xi) solving strategic issues related to lockdown.10 Each group consisted of senior officials from the Prime Minister’s Office and the Cabinet Secretariat.

As of November 4, 2020, at least 72 apps had been deployed by public entities in India across Android and iOS platforms, three of which can be used pan-India. Their functions, as per the features listed in their descriptions on the Android Play Store, in government notifications, media coverage, and existing research reports, include: contact tracing (4); quarantine monitoring (21); accessing essential services (12); disseminating information (34); self-assessment (25); e‑pass integration [display and/or application for e‑passes] (9); telemedicine (6); fund-raising (10); reporting gatherings/individuals (7); information gathering/surveys (12); displaying heat maps (2); displaying other information on maps within the app11 (6); providing the option to register as a volunteer (5).

Reflecting the mobility restriction measures that have formed the crux of Covid-management strategies in most countries, at least 30 of these apps affect the movement of users or of those in their vicinities, in the form of geo-tagging, requiring individuals to upload their selfies at fixed intervals throughout the day to verify their current location, asking users to upload photographs of their house, allowing the public to view the location of home-quarantined persons, offering an option to report violators of quarantine rules, allowing users to track the movement of Covid-19 patients in their vicinity, and so on. Twenty-seven of the apps have a dedicated privacy policy. For the remaining apps, the privacy policy is either not present, or it re-directs the users to the state’s or the developer’s website, or the link is not functional.

Other tech-enabled tools also joined the fray in the nation’s battle against Covid-19: drones, CCTV cameras, thermal scanners, online portals for travel registration, and more. The MoHFW updates their website with the number of active cases, including the number of recovered/discharged patients and deaths. By February 8, 2020, India had about 10.8 million confirmed cases of Covid-19, the second highest in the world, and about 155 thousand deaths.12

In this report, we will analyze some of these apps and tech-enabled tools across three main research considerations: (i) from a public health perspective; (ii) potential for function creep and social control, by both state governments and by non-state actors; and (iii) the perspective of equal access and participation of vulnerable groups in society.

METHODOLOGY #

This report uses a mixed method research design, drawing from both semi-structured interviews and desk research. We conducted in-depth interviews with a range of key stakeholders, such as those involved in the development and deployment of the app/tech-enabled measure, senior government officials, industry leaders, epidemiologists, and public health experts. The interviews were conducted in October and November 2020. Owing to severe limitations on travel and safety imposed by the pandemic, the interviews were conducted online and via phone. We were mindful that we were reaching out to these key stakeholders, particularly government officials, in the middle of a public health emergency. Many of them understandably had extraordinarily busy schedules, which limited the number of persons we could interview within the constraints of the project’s timelines. All interviewees were informed that the guiding principle for the report is that participants are in control of the disclosure of their identity.

Many of the primary sources cited in our report were not easy to locate, as they were scattered across official websites, personal social media handles of officials, and official social media handles, in a way that blurred lines between the personal and the public. Press releases and government orders regarding several key developments were also unavailable in the public domain.

Additionally, owing to the evolving nature of the pandemic, official decisions also changed in response to the needs of the hour. This was reflected in the apps and alternative measures that we analyzed − the governing documents of these tools were updated or changed, features and functionalities were modified, official websites were taken down, and in some cases the measures were removed altogether.

Our preliminary desk research and overview of media reports suggested that there were several apps and alternative means deployed for Covid-19 management. First, we conducted an extensive mapping process of both categories: we charted all the Covid-related apps that had been deployed by public entities, using information available on the Android Play store, and through government notifications, news reports, and existing research reports.131415[^16 ] We then followed a similar process for all technological and non-technological alternative measures.16

Covid-related apps

We found 72 apps in the country launched by central government, state governments, municipal corporations, and public research institutes.17 Of these 72, we listed each of the Covid-related apps that had hundred thousand or more downloads on the Android Play Store. This resulted in a list of 26 apps which we then shortlisted to those that stood out in terms of their functionalities, and those that were particularly relevant to this project’s goals. Finally, we subjected this new shortlist to a top-level analysis that asked: how likely is it that each theme that our preliminary research has deemed relevant will also be of relevance to this particular app? An overview of this analysis can be found here.18

Based on this process, it was decided that for this report:

● Aarogya Setu, which had been downloaded 100 million times on the Android Play Store, would be the primary focus.

● Three state-level apps would be briefly analyzed in light of one of their functionalities. They are: i) Quarantine Watch (asks for selfies from users); ii) CoronaWatch (public display of personal information); and iii) Corona Virus Alert App (COVA) Punjab (has a feature to report others).

In our preliminary mapping, we had to factor in certain practical considerations. First, some of the apps were in regional languages that we are not familiar with, which limited our ability to analyze their features and functions. Second, we did not download the apps for analysis, as some of their data privacy specifications were ambiguous.

As we have relied on the descriptions of the apps on the Play Store, along with secondary sources of information, we anticipate limitations as the information available could be incomplete: for instance, the descriptions on the Play Store were not always updated and the existing descriptions were not always reflective of the actual functioning of the app. To overcome these limitations to the best of our ability, we used additional sources of information, such as news sources, government press releases, and additional literature. For example, the description of Punjab’s COVA App on the Android Play Store does not list contact tracing as a feature; however, other official sources have listed it as one of the app’s functionalities.19

Alternative means

We also mapped all known technological and non-technological alternative measures used to combat the pandemic in the country. For the alternative measures, we factored in the following considerations: i) considerably less focus has been given in public discourse to technological tools that have been used to combat the pandemic, as opposed to means such as the nationwide lockdown, and ii) these tools contribute to a much larger tech-enabled ecosystem of surveillance, which could also outlive the pandemic.

Based on this process, the following tech-based alternative measures were selected:

• Drones: There was an increase in the use of drones − also known as Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) − during the pandemic, particularly by law enforcement authorities. Some of the drones were outfitted with cameras, as well as AI (Artificial Intelligence), such as thermal scanners.

• Online portals for travel, and the National Migrant Information System (NMIS): For this measure, we will focus on the NMIS, and engage with the use of e‑passes to the extent relevant for the NMIS. This report will look at these measures in the context of the migrant crisis that unfolded in India during the lockdown.

OVERVIEW OF APPS AND ALTERNATIVE MEASURES #

Aarogya Setu #

On April 2, 2020, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) announced the launch of Aarogya Setu, an app that uses a self-assessment by the user as well as GPS and Bluetooth technology to do contact tracing, hotspot prediction, and to conduct and display a risk assessment of the user. The app also has a range of other features, which include: i) integration with the e‑pass portals used by states for the regulation of travel during the lockdown; ii) live statistics related to Covid-19; iii) information on ICMR-approved labs with Covid-19 testing facilities and emergency helpline numbers; iv) information on government advisories, orders, and best practices related to Covid-19; v) APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) to allow users to disclose their health status by displaying a QR code or by accepting a request to share their health status; and vi) an option to donate to the Prime Minister’s Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations Fund (PM CARES), a privately audited fund established by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

MeitY’s official press release announcing the launch said that Aarogya Setu had been “developed in public-private partnership.”20 It described the app as being “a multi-dimensional bridge” that would “enable people to assess themselves the risk of their catching the Corona Virus infection.” Aarogya Setu is a Sanskrit phrase that translates as “the bridge to liberation from disease.” The app was initially released via the app stores on iOS and Android, and made available for KaiOS on May 14, 2020.

On May 26, in another press release, MeitY described it as a “contact tracing and self-assessment” tool, which was “pioneering new data driven epidemiological flattening of the curve through syndromic mapping.”21

Aarogya Setu was the fastest-growing mobile application in the world in April, clocking over 50 million downloads in the first 13 days and beating Pokémon GO’s world record.22 By July 2020, the app had been downloaded more than 127.6 million times.

The country’s government machinery was mobilized right from the beginning to promote the app. In a video conference with the Chief Ministers of all states to discuss the strategy for tackling Covid-19, Prime Minister Modi spoke about the need to popularize the app, and to ensure a high number of users nation-wide. He referred to South Korea and Singapore’s successes in contact tracing, and said that Aarogya Setu was “an essential tool in India’s fight against the pandemic.”23

When a user registers on the app, the Aarogya Setu server assigns them an anonymous, randomized unique Device identification Number (DiD) and associates it with their mobile number. This pair – the mobile number and the DiD – as well as other personal details provided at the time of registration, are encrypted and stored in the Aarogya Setu server. When a mobile device that has Aarogya Setu installed and the GPS and Bluetooth services turned on comes within range of another such device, the app collects the DiDs and details of the interaction such as time, duration, distance and location. This information is encrypted and stored on the device.

At the backend, the nodal agency for testing, the ICMR, gets the test results from the Covid-19 labs across the country. This database has a list of the registered mobile numbers of the patients who have tested positive for Covid-19, which is shared with the Aarogya Setu server. In the event of an Aarogya Setu user testing positive, the app pulls up the list of other users who have come in contact with them in the previous 14 days, calculates their risk of infection, and communicates that to them.

Users can also take a self-assessment test which evaluates the risk of infection based on the data points collected. The following information is requested in the test: i) whether the user has any Covid-related symptoms (the options for which are listed); ii) whether the user has any pre-existing health conditions;24 iii) whether international travel was undertaken in the last 14 days; and iv) whether the user has come in contact with someone who was infected with Covid-19 or whether the user was a healthcare worker who examined a Covid-infected patient without wearing protective gear.

The FAQ on the app’s website also states that Aarogya Setu collects the user’s location each time a self-assessment test is taken and that this information, along with the DiD and the results of the test, is stored on the server in an encrypted form.

The results of the risk assessment are shown on the home screen of the app in one of the following categories: i) green: low or no risk; ii) yellow: moderate risk of infection; iii) orange: high risk of infection; and iv) red: positive.2526

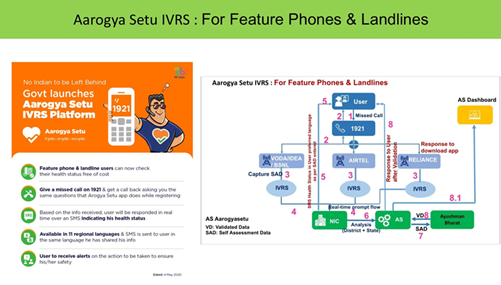

On May 6, the self-assessment option was extended to those who have access only to feature phones or landlines, through the Aarogya Setu Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS). Residents can give a missed call to the number 1921, following which they receive a call asking for their health details, along the lines of the questions on the app. Based on their responses, they receive an SMS indicating their health status.

Over time, new features have been continuously added to the app and existing features have been modified. On July 5, 2020, an update to the app introduced a feature for people to see the number of users who have been in Bluetooth-proximity to them, along with their risk levels. If a user’s screen turns yellow or orange, that is moderate or high risk, the app also provides details of the date, time, approximate location, and duration of contact with users that have tested positive for Covid-19.27

An e‑pass integration feature was also added a few weeks after the launch of the app,28 as were the “Aarogya Setu Mitr” portal and “Open API services portal.” The Mitr portal was launched in May 202029 as a public-private collaboration that offered free teleconsultation services, home delivery of medicines, and a feature to book Covid-19 tests. The service was suspended by the central government after the South Chemists and Distributors Association filed a petition at the Delhi High Court, which included complaints from close to 850 thousand brick-and-mortar retail chemists across the country alleging that the portal served as “a marketing tool for e‑pharmacies only and excluded marketing, distribution and sales by the offline chemists.”3031

According to a MeitY press release, the Open API services portal, introduced in August 2020, allows organizations and business entities to “query the Aarogya Setu Application in real-time and get the health status of their employees or any other Aarogya Setu User, who have provided their consent for sharing their health status with the organization. Subject to the user’s consent, the API provides the name and the status of the user.”32 This will be discussed in detail in Pillar 2.

Aarogya Setu has a dedicated website which contains major notifications and press releases about it, an explainer on how the app works, myths about Covid-19, the total tally of confirmed and recovered Covid-19 cases, the official death toll, and more.33 It also has an official Twitter handle which is routinely updated. Aarogya Setu is currently available in 12 languages, and the IVRS in 11.

State-Level Apps #

Aside from Aarogya Setu, the central government as well as different state governments have launched more than 70 apps with some states deploying multiple apps. As each of these apps is unique, and situated within the respective local ecosystem of the state, an in-depth analysis of each is outside the scope of this report. Instead, we will briefly analyze three functionalities, each with a focus on a different app.

QUARANTINE WATCH

By January 2021, the Government of Karnataka had launched nine apps to manage the pandemic: Corona Watch, Quarantine Watch, SRF ID, Containment zone, Yatri, Apthamitra, Health Watch, Daily Analytics and Reports Software, and Contact Tracing. The last three are for frontline workers.34

The Quarantine Watch app can only be used by home-quarantined people in Karnataka who have been registered in the state’s official database.35 The app requires users to answer a questionnaire to assess their symptoms, and to upload mandatory hourly selfies between 7 am and 9 pm to capture their GPS location, which is used to verify that they are quarantining.36 The mandatory selfies are the reason why we have included this app in our analysis.

The app was made mandatory at various points. For instance, one of the guidelines in the “Revised Guidelines for Home Isolation-Home Care of Covid Positive Persons” issued by the state government on August 10, 2020, required those in home isolation to use Quarantine Watch and Apthamitra as well as Aarogya Setu.37 Foreign returnees to the country were also required to download Quarantine Watch.38 According to the “Revised Protocol for Inter-State Travelers” issued by the Government of Karnataka on August 24, 2020, monitoring through Quarantine Watch has now been discontinued.39 However, at the time of writing, the app is still available on the Android Play Store.

CORONA WATCH

Corona Watch shows users the movement history of people who have tested positive for Covid-19 in the 14 days before their test.40 According to publicly available information, one section of the app has a map display, with the current location of the user visualized as a blue dot, alongside indicators of the travel history of Covid-positive patients, and the exact dates and times of their visit. Reports also indicate that the locations shown include the homes of the patients. This feature is the reason why this app has been included in our analysis.

The app also provides users with information such as the nearest designated hospitals for treatment and centers for Covid-19 sample collection and testing.

CORONA VIRUS ALERT APP (COVA) PUNJAB

The Government of Punjab has launched a range of measures, both technological and non-technological, to deal with the pandemic.41 The COVA Punjab app was one such measure, and was the first Covid-related app launched in India.4243 A Covid Response Report by the state says that as of August 20, 2020, 11 other states have asked “for access to the App and its features.”44 According to a tweet45 by the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of Punjab on March 28, 2020, the app was in the process of implementation in two provinces in Canada as well.

Based on publicly available information, the functionalities of the app are: a) geo-fencing of quarantined individuals; b) contact tracing of positive cases; c) identification of hotspots; d) allowing users to report mass gatherings and inter-state travelers in their locality; e) self-screening of symptoms; and f) display of government advisories, travel instructions, and statistics. The latest update of the app on Google Play Store allows users to obtain their Covid-19 test results as well. A recent government document also lists plasma donor registration as one of the functionalities.46 The feature that allows users to report others is the reason we have included this app in our report.47

While the contact tracing functionality of the app has not been described in the information available on the Android Play Store, official sources have listed it as one of the app’s features.48 An official in charge of the app has stated that contact tracing and GPS-based tracing is done “using the data available with us through the application.”49 The state is also using call record details of patients who have tested positive to trace anyone they might have had contact with in the 14 days prior to their test. There is very limited information available on the actual process of contact tracing used by the app. It has also been reported that the app uses a color coding for patients: “green for healthy, orange for suspect (cases) and red for confirmed cases.”50 An official press release also mentions that the app is integrated with the ICMR platform, Aarogya Setu, and the ITIHAS platform.51 The functionality that allows users to report others is the reason we have included this app in our analysis.

Drones #

Drones, including ones equipped with AI technology, have been used by government authorities for various purposes during the pandemic, such as enforcing lockdown,5253 identifying curfew violators,54 disinfecting public spaces,55 thermal scanning,56 and making announcements.

In April 2020, there were reports in the media that a task force called the National Drone Rapid Response Force (NDRRF)57 had been formed to connect state officials with drone pilots. The task force was described as a “public-private partnership”, in which approximately 400 drones across 30 companies, as well as freelance drone photographers, worked with local administrations and law enforcement authorities in multiple cities across the country to enforce the lockdown, make announcements, and disinfect spaces.

Online Portals and the National Migrant Information System #

ONLINE PORTALS

One of the primary methods that nations used to combat the transmission of Covid-19 was the enforcement of physical distancing and mobility restrictions. This was true of India as well. In order to regulate travel, particularly during the lockdown, central and state governments introduced online portals and apps for people to apply for e‑passes, emergency passes, vehicle passes, or other confirmations (such as SMS messages) to be used as proof of permission to travel. Many of these measures continued to be in place even as the country slowly opened up. The e‑pass/permit served as an indicator that the user had permission to travel for the specific reason mentioned in their application.

By the end of May 2020, at least 29 states and union territories had opened their own online portals where people could apply for these e‑passes for inter- and/or intrastate travel.58 Each state and union territory had different requirements, forms and self-declarations, mobility restrictions were imposed and enforced differently in all of them, and it appears there was no standardization of the kind of information asked. In some states, a separate link for registration was available for particular groups of stranded people, such as laborers, students, etc.59

The National Informatics Centre (NIC) also designed and developed a centralized portal for the “e‑pass for movement during lockdown.”60 As of November 20, 2020, there were 20 states and union territories listed on the national e‑pass portal, which suggests that at least 20 had linked their own portals to the NIC at some point. The portal directs the user to the respective state government’s website, and states that ownership of data would “lie with the respective state governments.” Powered by ServicePlus, the portal, as of November 20, says that it has received 4,424,934 applications, of which 1,798,346 were given permission to travel, 1,200,133 were being processed, and 1,426,455 were rejected. There is no information about when these counts were last updated, or why passes were rejected.

As the country moved towards reopening after the lockdown, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued a statement on August 29, 2020, that there would no longer be any restriction on inter-state and intrastate movement of people and goods, and no requirement for separate permissions/e‑permits. They added that states and union territories were not to impose any local lockdowns outside containment zones without prior consultation with the central government.61 Though the NIC e‑pass portal is still up, many of the links to the existing state portals are non-functional.

THE NATIONAL MIGRANT INFORMATION SYSTEM

In addition to these online state websites for travel registration and portals, in the month of May a central repository named the National Migrant Information System (NMIS) was launched by the National Disaster Management Authority. This was in response to a humanitarian crisis that unfolded in the country once the lockdown was declared, as millions of migrant workers found themselves without a source of livelihood, hundreds of miles from their hometowns. Many of them were forced to journey home over the next few weeks, travelling across different states in order to do so. The NMIS was started to enable coordination between various states and transportation systems. The migrant crisis will be discussed in detail in Pillar 1 of the report.

Besides a letter addressed to the Chief Secretaries of all states from Home Secretary Ajay Bhalla, there has not been any other official documentation about the NMIS. Moreover, this system can only be accessed by state officials, and not by the general public. Thus, this report will rely on the information provided by the letter, the response to a subsequent Right to Information (RTI) request filed by MediaNama, and interviews with a senior government official and two members of a volunteer group that provided relief to migrant workers stranded due to the Covid-19 lockdown.

The letter from the Home Secretary described the NMIS as a central repository to “capture the information regarding movement of migrants and facilitate the smooth movement of stranded persons across States.”62 The letter also described the features and benefits of this portal as:63 “Standardised system, seamless communication and coordination between different states, easy access to databases by Railways and other transportation management systems, generation of e‑pass through centralised system, easy monitoring of stranded persons etc.” It also notes that this system would help states visualize the number of migrants travelling in or out, and help states plan the logistics between themselves and the Ministry of Railways.

As for data collection, the letter said that state governments could appoint nodal officers at the state and district levels to upload data onto the portal. Alternatively, states could also share data through an API if the state already had a portal.

According to the annexes accompanying the letter,64 states are required to provide the following information: “i) Name ii) Unique ID (to be generated from the NDMA System) iii) Mobile number iv) Aadhaar number65 v) Age vi) Sex vii) Whether Migrant labour, student, tourist, pilgrim, etc. viii) Current address ix) Origin state x) Origin district xi) Residential/permanent residence xii) Destination state xiii) Destination district xiv) States on the route (in case of bus journey) xv) Mode of transportation xvi) Bus/train number xvii) Date of journey xviii) Coach number, in case of train xix) Expected date and time to reach destination.” However, according to the response received in the RTI filed by MediaNama, the states can upload the following information: “i) Name ii) Gender iii) Age iv) Mobile Number v) ID type vi) ID number vii) Migrant Origin District viii) Migrant Destination District.” The RTI also notes that it is not mandatory for states to upload the information.66

PILLAR 1. APP RESPONSES AND ALTERNATIVE MEANS — PUBLIC HEALTH PERSPECTIVE #

The Indian Constitution mandates healthcare to be a state rather than a Central Government responsibility.67 This makes the healthcare system in the country uneven, with a few states having more highly developed structures in place, while the majority lag behind.

India’s healthcare infrastructure is organized into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels: Sub-Centers and Primary Health Centers (PHCs) at the primary level, Community Health Centers (CHCs) at the secondary level, and Medical Colleges and District/General Hospitals at the tertiary level. There is also a large network of sub-primary level community healthcare workers on the ground, instituted through programs that date back to 1977.68 Currently, the largest group of community health workers are the over one million women who have been trained as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs, which translates as “hope” in several Indian languages), through a National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) program that began in 2005. They are frontline workers tasked with the job of promoting access to improved healthcare at the household level,69 in accordance with the NHRM’s mission, particularly in rural and “rurban” areas.

The Indian healthcare system is not new to pandemics or widespread public health challenges. Malaria, dengue, drug-resistant tuberculosis, chikungunya, leprosy, HIV, mumps, measles, and high maternal and child mortality rates, for instance, are only some of the concerns that it has been handling – with varying degrees of success – in the last seven decades. But Covid-19, with its high rates of transmission, has thrown the cracks in the healthcare system into stark relief. According to the MoHFW, the country’s doctor-population ratio was 1:1456 in August 2019, as against the WHO’s recommendation of 1:1000. They also state that the urban to rural doctor density ratio is 3.8:1, and that consequently, “most of our rural and poor population is denied good quality care, leaving them in the clutches of quacks.”70 World Bank statistics from 2011 estimate that India has, on average, 0.7 hospital beds per 1,000 people.71

Even though public healthcare in India is funded by taxation and free for residents, the National Family Health Survey (NFHS‑3) of 2005-06, released by the MoHFW, states that private healthcare systems remain the primary source of healthcare for 70% of households in urban areas and 63% of households in rural areas.72 A study conducted on the same NFHS‑3 data revealed that the elderly, women, people who had lower levels of literacy, low-income communities, and other marginalized groups were more likely to use public healthcare than private.73 Yet, according to a report by the Center For Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy, most ICU beds and ventilators are found in private hospitals, with a high proportion of them concentrated in just seven states.74

Early on in the pandemic, the central government as well as various state governments launched technological measures as part of their healthcare management efforts. In March, the Department of Science and Technology (DST) set up a Covid-19 task force for:

“Mapping of technologies from R&D labs, academic institutions, startups, and MSMEs to fund nearly market-ready solutions in the area of diagnostics, testing, health care delivery solutions, equipment supplies. Some of these solutions include masks and other protective gear, sanitizers, affordable kits for screening, ventilators and oxygenators, data analytics for tracking, monitoring, and controlling the spread of outbreak through AI and IT based solutions, to name a few.”75

Public health experts contend that overall, the push for digital measures was happening without a parallel investment in the country’s basic health infrastructure. Dr. Thelma Narayan, an epidemiologist and health policy analyst, said:

“Why have we not invested in our public health system? People have been crying themselves hoarse on the need to strengthen the public health system. Why do Indians have one of the lowest… proportional GDP for health in the public health system? Ours is immorally and scientifically low, i.e., much below norms recommended by the WHO. It’s 1.1% of the GDP that goes to the public health system, and then you expect to counter pandemics. One can’t do that.”76

Per capita government spending on healthcare has doubled from INR1,008 (approximately USD13.85) in 2015 to INR1,944 (approximately USD26.72) in 2020. However, the numbers are still low.77 Rukmini S., an independent data journalist, stated that the lack of adequate administrative and health infrastructure had impeded the state’s ability to respond to the epidemic:

“The basic point that has been inescapable, but that of course the government has never owned up to, is that it simply lacks the state capacity to pull off most of the things that were essential, and that it seems to be indicating that it wanted to do – which is to increase both administrative and health infrastructure capacity, [which] are abilities that the Indian state currently just simply does not have. And you see it in the richest of cities, in Delhi and Bombay, for example, just the ability to create a dashboard of availability of beds took halfway into the pandemic to be able to get there. And it’s still not a reliable system, because of the huge range of vested interests and competing, conflicting interests that may govern healthcare in India.”78

The nationwide lockdown announced on March 24, 2020 was ostensibly to help India’s underfunded, understaffed healthcare system prepare for Covid-19, as well as to prevent the system from getting overwhelmed. However, it led to several unintended public health consequences, as well as a larger humanitarian crisis of hunger,79 and the escalation of gendered violence inside households, which reached a ten-year high.80 Gunjan Singh, a labor rights lawyer based in New Delhi, said:

“Initially, you had hospitals closed, OPDs [Outpatient Departments] were closed, so all those people who wanted to have a routine check-up – people who had blood pressure issues, thalassemia patients, and a lot of HIV positive cases where people have regular medication – [couldn’t]. We had to file petitions for those services to be started – because they had just closed down everything to contain the virus. You need to have a better plan.”81

Others highlighted that data collection was critical to understand the impact of the virus and to respond adequately, and that the need of the hour was for simple, factual data from the ground. An epidemiologist with the ICMR noted:

“Terminologies like modeling, artificial intelligence, machine learning have zero role in terms of Covid-19, because it is not about technology, it is not about capacity, it is not about expertise, it is about data…The simplest expertise which is required, [at] the ground level, is to capture the actuarial factual data from the field. People are not concentrating there, people are concentrating on building models, building AI and all…For Covid-19 monitoring, we don’t require a…higher level of portal, we request [a] simplistic portal. What is simplistic? We collect actual data and factual data. Let us analyze very descriptive data − that is enough. Simple proportions, simple maps, not like kind of high funda maps, simple proportions, simple graphs, simple bar charts. And these are the things that [are] required. But many governments have heavily invested [in] multiple high funda portals, high funda maps, or GIS maps and everything.”82

However, a senior government official stated that the lockdown, as well as the use of data and technology, had helped delay the peak of the pandemic, and given them time to prepare:

“I think the main advantages of the early action which the Government of India took, including the imposition of restrictions on movement and contact tracing and quarantining [people] suspected of [having Covid], and people at risk, all those. One of the main advantages was that it delayed the peak and gave hospital infrastructure time to be ready for responding to the crisis. Because if the number of cases which we saw later [had] come in March or April, then our infrastructure may have been at a very high stress. So we were able to delay the peak, that’s number one.

Number two, we were able to make the state government and district authorities aware about the hotspot or sensitive districts, so that they can make their strategy accordingly and they can use their resources in [an] appropriate manner. And the use of technology, it was perhaps for the first time in India that such use of technology was done. But then it gave us an idea about areas which can be at higher risk. In fact, we were even able to see [the] movement of specific suspected people and if they have gone into a particular gathering today or something like that. Since initially the number of cases was not very high, we could identify people who are at higher risk and warn them and advise them to get tested, right. Again, it gave us a very positive result, at least in the beginning.”83

EFFICACY OF APP RESPONSES FROM A PUBLIC HEALTH PERSPECTIVE #

Aarogya Setu #

Aarogya Setu has been widely promoted by the government as India’s “bodyguard” against Covid-19.84 In this section, we assess the design, features and functions of the app that are relevant from a public health perspective.

Contact tracing

For decades, contact tracing has been one of the cornerstones of communicable disease control in public health. Aarogya Setu was one of hundreds of apps that were released all over the world in the wake of Covid-19 for digital contact tracing.

The central government has maintained that Aarogya Setu has been an indispensable tool in its fight against Covid-19, and that by leveraging modern technology, the app has aided the efforts of medical and health professionals. An official press release dated May 26 described the app as “possibly one that has the most reach and impact compared to all other Covid-19 contact tracing and self-assessment tools combined globally.”85

At the same time, the developers of the app have also acknowledged that there are limitations to what an app can do, particularly in the Indian context. In a webinar in April 2020, Arnab Kumar, Program Director at NITI Aayog, a government think tank, and member of the Aarogya Setu team, clarified that: “Smartphone-based contact tracing cannot replace manual contact tracing for a country as diverse as India.”86 Some of the major challenges that have been pointed out by public health experts and epidemiologists, as well as the government’s responses to them, are discussed below.

a) Adoption of the app: Challenges and government responses

An international scientific consensus has emerged that the relative success of a contact tracing app depends on its uptake within the population. Though studies have shown that a critical mass of users is vital,87 there is little evidence on the minimum percentage of users needed to ensure accuracy.88

In India, members of Aarogya Setu’s development team have stated that the “effectiveness of the app would be limited unless a large number of people download the app,”89 with one member arguing that “at least 50% of the population needs to download the app for it to be effective.”90 This has been echoed by civil society members as well, who have questioned the feasibility of reaching such high numbers in a country where only about 40% of the population have a smartphone,91 and less than 36% have access to the internet.92

One of the clauses in Aarogya Setu’s Terms of Service states: “You agree to keep the mobile or handheld device on which the App is installed in your possession at all times and to not share it with or allow anyone else to use it. You acknowledge that if you do so it could result in you being falsely assessed as likely to be infected with Covid-19 or not being assessed as such when you are.”93 But in India, it is not uncommon for households to share a phone amongst family members.94 These socio-economic realities, particularly for those who are marginalized, affect access to and the effectiveness of technologies such as a contact tracing app.95

The developers of the app have acknowledged this issue. In an online webinar, one of them said:

“This being a function of social distancing, I think predominantly we have a lot of rural districts, and the spread has been in metros first as you see in Delhi, Madras, Chennai, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, large cities, and then tier B cities. So, we are going to get this app done in many of the congested areas and densely populated areas even within cities, then I think that would be an excellent contribution. Rather than saying that the entire country of 120 crores [1.2 billion] should have the app, if we say that, within one particular area of this population density, highly congested areas, if those areas get it, I think that will certainly reduce the incidence…We agree that we need a lot more members to use it to make it effective, but effectiveness cannot be just a percentage of the population, but [rather] a percentage of the distribution of the population. And the density of the population…We still believe that once the congested areas get this, at least Wave 2 can be stopped in a very constructive way.”96

The issue of uptake is also gendered, given that women in India are 20% less likely than men to own a mobile phone and 50% less likely to use the internet.97 While this will be discussed in detail in Pillar 3, it is important to note the public health ramifications of what is one of the largest mobile gender gaps in the world.

Disability rights activists have pointed out that the app is inaccessible for people with disabilities.98 The Vice-President of the National Association for the Blind, Dipendra Manocha, said: “If you exclude the disabled population from something as critical as this, you are putting not only them but the entire population at risk. It can have a huge impact on the government’s Covid response.”99 The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016 makes it mandatory for the government to provide all information in accessible formats for the benefit of people with disabilities, but there have been no reports of any modifications having been made to the app.

The app also requires users to be able to navigate the technical features of the phone, since for efficient contact tracing, the app recommends that Bluetooth and GPS location be turned on. Certain sections of the population, such as the elderly, may find it challenging to navigate these requirements.

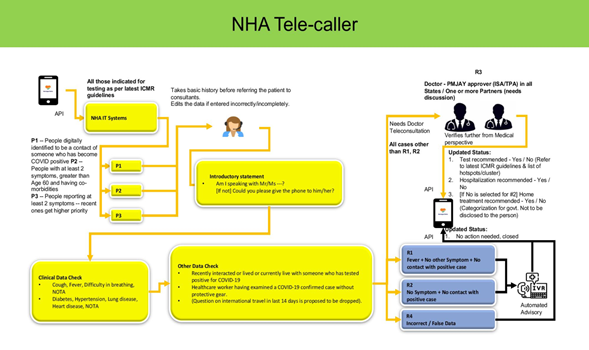

One of the government’s bids to make the app more accessible has been the Aarogya Setu IVRS feature for feature phone and landline users.100 There is no publicly available information on the number of users who have accessed this self-assessment system. But as per the FAQ section on the app’s website, those who report that they are unwell through their self-assessment get calls from doctors, as well as from Ayushman Bharat Yojana, which is a health insurance program implemented by the National Health Authority (NHA). This will be addressed in Pillar 2.

Early on in the pandemic, the government had made Aarogya Setu mandatory for all residents of containment zones, as well as all public and private sector employees.101 However, civil society members pointed out that making it mandatory violated the spirit of the consent-based agreement that users sign when they register on the app. The government order was amended, making it voluntary, though there have been several instances since of the app having been made mandatory or strongly recommended by different central and state government bodies, as well as by and private institutions.102

The pushback against the mandatory nature of Aarogya Setu also indicates that in an emergency context – and possibly especially then – governments need to engender trust and transparency to ensure the support and cooperation of their people. In other words, the adoption of the app would also depend on the level of faith people have in the system.103 Aarogya Setu has been under international scrutiny over privacy concerns over the last few months, with various claims that the app lacks transparency and is intrusive.

This will be addressed in detail in Pillar 2. An Aarogya Setu Volunteer104 stated that building trust amongst the public was a vital and difficult part of their work:

“[Trust] is a very tricky affair because [in order] for me to show that this is effective, I need the people to install it, and for the people to install it they need to know that it is good for them… Sometimes [people] should believe that ‘Okay, so many people are involved. There is a problem in hand. Let us try and see.’ See, the government did not mandate it. They have certainly valued the privacy and freedom of citizens even during the critical pandemic.”105

They stated that concerns about data privacy and security of the app had affected its usage and downloads:

“Today, we are having 16.73 crore [167,300,000] users. It is the largest downloaded software, but it could have been 30 crore [300,000,000]. This type of sudden noise actually made the whole process [difficult]. It was unfortunate that people were given this fear saying that if you install Aarogya Setu, [there will be] surveillance etc., that type of fear. [But] you can delete that app any moment you want, you can delete and reinstall it anytime you want. What more can we do? So, all this is a big lesson. We don’t want this. This stupid pandemic should end in these next few months. But, beyond this, the next century, again, [if] something ever comes, next century people should understand what is happening and not make the same mistakes.”106

We asked epidemiologist and health policy analyst Thelma Narayan if a contact tracing app with a sturdy privacy and data sharing protocol would be a useful public health measure from an epidemiological point of view in India. She replied:

“No, it would not. One has to keep in mind that the smartphone users don’t cover the whole population. It automatically leaves out, not just the homeless, but a huge number of people who don’t have smartphones. From an epidemiological point of view, you’d want to have more or less wide coverage… I don’t think digitization, which is promoted by a particular lobby, is actually going to help.

Additionally, besides the issue of access, digitalization is accompanied by a range of other issues. These include significant anxiety and loss of self-confidence which affect the mental health of senior citizens, persons with disabilities, and large section of the society. It can also be widely misused. Thus, it contributes to a widening of the equity gap.”107

Sunita Bandewar, a bioethics expert, also echoed this, saying:

“If you look at the utility and the effectiveness or the efficiency of these apps in terms of meeting the goal, it is also linked to the adequate number [of users]. If everyone is not using the app, for whatever reason, [then] that is also a very solid ground to discontinue the app. That is a question that is being raised in the bioethicist community: what is the use of this app if we are not able to achieve that critical mass of users?”108

Government officials have continued to express deep confidence in Aarogya Setu, and the role it has and will continue to play in pandemic management in India. Aarogya Setu Volunteer #1 said:

“Today, I can basically handle disease spread if people [download it]. Even now, it’s not [too] late. The whole world is seeing Wave 2.0. India can come out of Wave 2.0 if everyone installs Aarogya Setu.”109

b) Bluetooth-based contact tracing

The app relies on Bluetooth technology as well as GPS location data for contact tracing, syndromic mapping and, as per the app’s website, for extending medical services and for disinfection of places travelled to by Covid-19 positive patients. An Aarogya Setu Volunteer explained why Bluetooth was chosen for contact tracing:

“The best proximity evaluation that could happen today is Bluetooth. And that is already available. We [didn’t] want to do something new. Something that people already have, some device [which people already have], can we also use it for this purpose? And if you look at it, Bluetooth was the best candidate.

We can measure two things: how close two phones in which Bluetooth is enabled are, and how long were they at this distance. So Bluetooth actually gave a good solution for our sensing problem.”110

About a month after the app was launched, Arnab Kumar stated that insights drawn from Bluetooth-based contact tracing had been useful for framing subsequent public health responses:

“The insights generated by Aarogya Setu in the last six weeks have been incredible. More than 100,000 people have been alerted of their possible risk of infection – low, moderate or high, based on Bluetooth-based contact tracing – and suitable medical facilities have been extended to them. The efficacy of testing based on initial recommendations from Aarogya Setu is many times higher than any other protocol followed globally. In addition, we have identified several potential emerging and hidden hotspots across the country.”111

Most digital contact tracing apps released all over the world in 2020 use Bluetooth technology. The European Commission has also recommended the use of short-range technologies such as Bluetooth for contact tracing.112 (However, it also cautions against the use of GPS, as in the case of Aarogya Setu, for reasons of privacy protection. This will be addressed in Pillar 2.) Nevertheless, from a public health perspective, the very inventors of Bluetooth technology have raised concerns about it being used for contact tracing, citing its inaccuracy in determining distance and how its signals are absorbed by everything from human bodies and clothes to walls.113 This concern has been raised by other experts as well, who have pointed out that apps that exchange digital handshakes through Bluetooth could notify people on different floors of an apartment building that they are at risk, even if they have not been in contact with each other, because it registers as a proximity event due to Bluetooth signals.114 Even the orientation of your phone makes a significant difference: if your phone is standing up in your pocket, portrait rather than landscape, it can make it look as if somebody across the room is just a couple of feet from you.115

Shubashis Banerjee, Bhaskaran Raman, and Subodh V. Sharma, Professors of Computer Science and Engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi and Bombay, have echoed several concerns about the reliability of these technologies in their assessment of Aarogya Setu, specifically about the possibility of false positives and false negatives.116 They point out that “it is unclear what interval rate of radio transmission is adequate for effective risk assessment of direct person-to-person infections,” and that too frequent transmissions will drain batteries, while too wide gaps in time will lead to false negatives.117 They also note that the risk of false positives/negatives also exists when there is an inaccurate representation of the distance. For instance, signals picked up over a large distance may not be reflective of the true risk, leading to a case of false positive. Third, the Bluetooth-based proximity sensing that Aarogya Setu relies on is not sufficient to account for the indirect transmission of the virus, such as through contaminated surfaces.

Receiving multiple alerts that turn out to be false could lead to warning fatigue, and lead people to dismiss the app’s notifications. On the other hand, a false negative could also create a false sense of security, and lead individuals who have already been exposed or infected to continue interacting with others and accessing public spaces, thus increasing the risk of the virus being spread. Banerjee, Raman and Sharma concluded that this over-reliance on Bluetooth and GPS may do more harm than good, especially with the low numbers of smartphone users in India:

“Such high noise may actually create confusion and detract from the main effort by sending administrators and policy-makers on a wild goose chase. It seems entirely unlikely that such apps can do anything for estimating risk of infection at the micro-level that local community-based manual contact tracing cannot do much more effectively.”118

The app’s Terms of Service recommend that users keep their Bluetooth on at all times for the app to efficiently record Bluetooth contacts. Experts have flagged that this could lead to draining of the phone battery, and potentially discourage people from using the app. The “Frequently Asked Questions” section of the app’s official website addresses this concern and clarifies that the app uses a Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) variant, which does not drain the phone’s battery, and that continuous efforts are being made to increase the app’s energy efficiency. Though there are possible exceptions, the BLE variant that many contact tracing apps – including Aaroya Setu – use has been standard in most phones, across operating systems, since 2012.

The developers of the app are also cognizant of the technical limitations of Bluetooth,119 and have stated that extensive testing was carried out prior to launch, across thirty smartphone models, keeping in mind India’s diverse phone base, to account for these performance issues. In an online webinar,120 in response to a question about the efficacy of Bluetooth, one of the app’s developers mentioned that they use a slightly more pessimistic model when it comes to assessing risk based on Bluetooth tracing, so that no one is left out, and more testing is carried out.

An official press release dated May 26, 2020, states that the app has helped in the identification of 500 thousand Bluetooth proximity contacts. Additionally, it says:

“Those who were identified as Bluetooth contacts of Covid-19 patients or are needing assistance based on their self assessment, are contacted by the National Health Authority. So far, the platform has reached out to more than 900,000 users and helped advise them for Quarantine, caution or testing. Amongst those who were recommended for testing for Covid-19, it has been found that almost 24% of them have been found Covid-19 positive. Compare this to the overall Covid-19 positive rate of around 4.65% – 145,380 Covid-19 positive from a total of 3,126,119 tests done as of 26th May 2020. This clearly illustrates that contact tracing is helping focus efforts on those who need testing and this will greatly augment the efforts of the Government in containing the pandemic.”121

Subsequent press releases from the government have continued to document similar success stories. According to a press release on the app’s Twitter page on October 28, almost 25% of those who had been traced using the app and had been advised to go for testing had indeed tested positive.122 A similar statement was made on August 22, in which the percentage of accuracy was identified as 27%.123

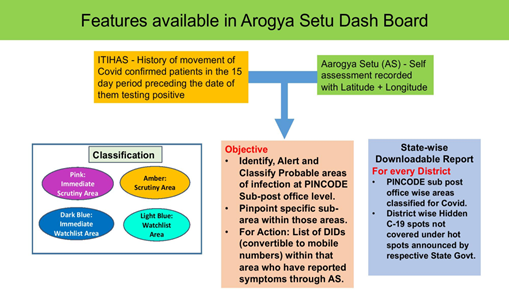

ITIHAS and hotspot-mapping

One of the primary stated objectives of Aarogya Setu is syndromic mapping and hotspot prediction. On May 11, 2020, in a press briefing by the Chairperson of the Empowered Group on Technology, a reference was made to the name “ITIHAS” in the context of identifying “probable areas of infection.”124 While there was no additional information regarding what ITIHAS was, he also added that an app had been developed for field officers to view hotspots and containment zones on a map.125 While the app was not mentioned by name, desk research indicates that it may be the Sahyog App.126

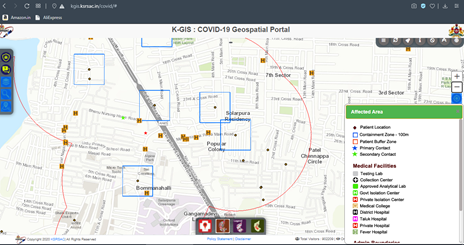

Figure 1. Image Courtesy of a Presentation by the Chairperson of the Empowered Group on Technology, May 11, 2020

On May 13, in an op-ed piece, Rahul Matthan, who heads the legal team behind Aarogya Setu, said that by “analysing the location history of the infected and aggregate self-declared symptoms of users collected via the self-assessment feature on the app, the team has been able to forecast over 650 hotspots across the country at a sub-post office level.” He also said that 130 of those hotspots had been officially declared as such by the Union Health Ministry 3 to 17 days after they were first identified by the Aarogya Setu team.127

On July 24, the Directorate General of Health Services issued an order to Chief District Medical Officers and Surveillance Officers of all districts, stating that Aarogya Setu would be combined with an “IT-driven tool” named ITIHAS, for cluster projection. The order also mentioned the full name of ITIHAS – IT-enabled Integrated Hotspot Analysis System – and said it was meant to boost the surveillance of Covid-positive people, and improve contact tracing. It added that the ITIHAS system was anchored by MeitY, and that it was “capable of tracking the movement of the cases and their contacts. The system is capable of projecting a cluster development in 300 metre geography.”128 Newspaper reports from the end of June indicate that the tool was first used in Gujarat as early as May 2020, and subsequently in multiple states all over the country.129

We asked Aarogya Setu Volunteer #1 about ITIHAS, as information about it is still thin on the ground. They responded:

“ITIHAS is nothing but the backend of Aarogya Setu. ITIHAS collected Aarogya Setu information, and performed syndromic mapping and hotspot prediction. This data that we are collecting, we put it to good use in terms of mapping hotspots. [ITIHAS] basically collects all the self-assessment, [and] from the location information, it does the mapping on to this sub-post office level. And then there are designated health workers across the country, designated by the health department of every state. They are given login to this portal, and they get this information.

… So say, in this particular location…we noticed there are so many self-assessments coming today. So, this place has some issues…So let’s go and do some testing there. This is called syndromic mapping. We were able to find out these hotspots, go to these hotspots. Catch early, contain early was the thing.”130

Another volunteer from the Aarogya Setu team added that they had always known that the generation of heat maps was critical:

“As much as contact tracing was useful, it had its challenges. We knew it up front, because no more than 50% of the population of the country has smartphones, and you need smartphones in order to be able to do this. And then even at that we are a billion people and at its height, there were 160 million people who used Aarogya Setu, and the numbers just don’t add up. You need maybe not 50% of the population to have a contact tracing app for it to be effective, that’s what some people say; maybe it’s still effective at, you know, 20 – 30%, but we are still short of that number. And there were challenges with that. So, as much as contact tracing was interesting, to me, it was the heat maps that were always going to be the more effective way of doing this.”131

Various press releases from the government have continued to echo claims of the app’s success with regard to helping in early testing and identification of hotspots, which has helped to channel medical interventions more efficiently:

“This approach of syndromic mapping, a novel approach of combining principles of path tracing and movement patterns of Covid-19 positive people, population level epidemiology modelling and the prevalence of Covid-19 in different regions of the country, the Aarogya Setu team has identified more than 3,500 hotspots across the country at sub-post office level. The Aarogya Setu data fused with historic data has shown enormous potential in predicting emerging hotspots at sub post office level and today around 1,264 emerging hotspots have been identified across India that might otherwise have been missed. Several of these predicted hotspots have been subsequently verified as actual hotspots in the next 17 to 25 days.”132

While the government has released data on the number of hotspots and the associated benefits of identification, it has not released any specific information on where these hotspots are, or what action was taken in these locations. One of our interviewees, an independent journalist and researcher who works on privacy and cybersecurity, pointed out:

“Mr. Abhishek Singh, who’s the CEO of [the] National eGovernance Division (NeGD), [had] said that we [have] tracked so many hotspots, but we have never been told the names, despite asking: Which were these hotspots that you predicted, and therefore prevented from happening? So there’s a lot of opacity around that. And that’s quite concerning.”133

An epidemiologist with the ICMR said that using Aarogya Setu’s data for hotspot prediction was important to attempt, even if no one could be sure of the reliability of the results:

“I would say it is a good exercise. [If we have data from] even 10 percent of [Aarogya Setu] users, [then that is] 1.2 million [people]. It is a very good number. It’s very good data, which is worth analyzing. The reliability of this, no one knows the answer. No one knows the answer, whether that is really valid data, no one knows the answer. But it’s worth the training and exercise, there is a lot of learning, in a pandemic, it is a process of learning, there is no one [who] knows a concrete answer. Things have fallen, and the systems have collapsed. So in a pandemic situation, it is worth trying everything, if the data is factual. With the factual data, it is really worth trying.”134

During a speech in October 2020, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director General of the WHO, spoke about various digital technologies that were being used the world over to combat Covid-19, and mentioned Aarogya Setu as well, saying that the app had “helped city public health departments to identify areas where clusters could be anticipated and expand testing in a targeted way.”135

Self-assessment test of health status

In addition to contact tracing, Aarogya Setu allows users to self-report their symptoms through a questionnaire based on guidelines issued by the ICMR. The app was updated to include a feature that allows users to view the number of people who had taken a self-assessment test in their vicinity, as well as the number of those who are unwell based on the self-assessment.136

Public health experts and other civil society members have pointed out that the effectiveness of public health measures that rely on self-reporting depends on users answering the questions truthfully. An independent journalist and researcher noted:

“A lot of it, of course, is dependent on people being truthful in these self-assessment tests. But if I’m a Zomato delivery driver, and I know that my job during a pandemic is dependent on me having the green status or having a clean status in this particular app, chances are that I would start gaming the system. Maybe I coughed 10 times today, but I won’t let the system know. I wouldn’t blame the person because he or she also has to earn and we know the economy is down in the dumps. It’s affected people belonging to working classes disproportionately more than it has affected people in the service class. So how do you make this work?”137

An epidemiologist with the ICMR also stated that all self-reporting is inherently subjective:

“All self-reporting is subjective. So the answer [to your question on how factual self-reporting is] is that because it is not factual, that by design, we accept that uncertainty.”138

Calculating and displaying the risk status of a user

While the self-assessment test is one of the app’s main features, it is important to note that users cannot choose their health status on the app (Green/Yellow/Orange). They can, however, choose to report themselves as Covid-positive (Red). The app uses an algorithm to calculate the probability of infection risk, and then categorizes users based on a range of factors, including the result of the self-assessment as well as contact tracing data. While there is no information in the public domain about the exact nature of the algorithm, the developers of the app have said it was created “by a set of experts who understand mathematics, population level statistics, epidemiology, medical doctors,” with insights from ICMR.139

Arnab Kumar highlighted that while there have been success stories, the team acknowledged certain constraints to the algorithm’s success, noting that the model is continuously updated. In response to a question on the reliance on an algorithm, he stressed that:

“This assessment was a ‘probability of risk’ and not a ‘possibility of risk.’ People need to understand that. The true indicator of whether you have Covid or not is a (medical) test. What we are trying to do is help you with intelligence. And people should understand, including people in civil society, we are not trying to solve everything through one app. That is not possible at all. It is a technology solution for intelligence.”140

Users do not need to mark themselves as Covid-positive (Red) as the app can do that automatically, using ICMR data. Aarogya Setu Volunteer #1 explained that while this feature has been met with criticism, citing MIT Technology Review’s study of contact tracing apps from around the world,141142 this had been adopted on purpose, based on a number of practical considerations:

“[They said] ‘A’ should come and self-declare that he is positive. Now, we started evaluating [our] options. Day in and day out, we are getting fake news, fake information, so many things. The flip side of this is that, suppose [if] I want to create chaos in society, I can install Aarogya Setu and go into a large crowded area. And by standing there, I am getting exposed to 500 people. Now, I [could] go and self-declare myself as positive and all those fellows will get warnings. By [doing] this, you can create chaos in society. So we weighed these two options. We found that the first option is better. Let a centralized system take the [information] from an authentic source and certify that somebody is positive.”143

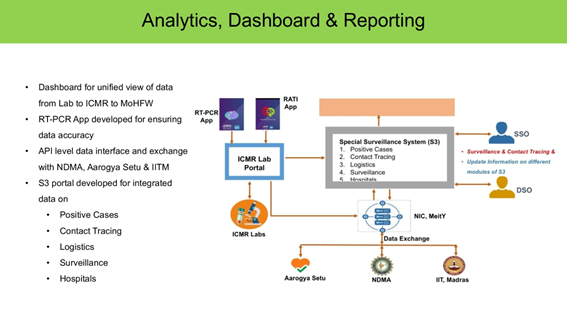

However, an option for users to upload information about their samples having been collected for testing, or to mark themselves as Covid-positive, was introduced in late April 2020. Officials have also stated that follow-up calls from medical professionals are made to those who do so, to ensure a greater degree of certainty. The following image from a presentation by the Chairperson of the Empowered Group on Technology demonstrates how this is done:

Figure 2. Image courtesy of a presentation by the Chairperson of the Empowered Group on Technology

Since users have very little control over their health status on the app, it is important to note that both false positive and false negative cases have been reported. While it is difficult to ascertain the exact reason behind each case, this raises concerns about the efficacy of the app.

In one case of a false positive, a woman was moved to a quarantine facility based on an alert generated by the app.144 She eventually tested negative and was released. She maintained that she “did not upload anything about her medical history, and neither had she received any notifications from the app regarding her condition.”145 In another case, a couple was incorrectly declared Covid-positive by the testing center, leading the app to update their status. It was reported that the app continued to show them as positive even after their health status was clarified, and they eventually lost out on a job opportunity owing to this.146 There have also been reports of the app not showing positive cases in the vicinity, even though someone was known to have tested positive there.147

Additionally, the mobile phone number that users provide at the time of registration on the app is the one that is checked against the ICMR database of Covid-positive patients. An incorrect number at any stage could result in misidentification, since the app determines the health status of the user. In an interview, on being asked whether they had received any grievances or complaints regarding the functioning of the app, Aarogya Setu Volunteer #1 had this to say:

“Sometimes what happens is [that] if the aged father is admitted, the mobile number of the son is given. When the son carries the [phone with] Aarogya Setu, it shows that he’s infected. This type of issue comes [up] and it’s immediately addressed. This is [similar to] when I give my mobile number for my father because he doesn’t have a mobile, and [his] test results are coming to me, and not to him. I think this is one major thing that you know, some people, even my friends, called me and said, ‘Sir, this is the problem’, and within 15 – 20 minutes it is fixed.”148

They added that this was the nature of the most frequent complaints they had received.

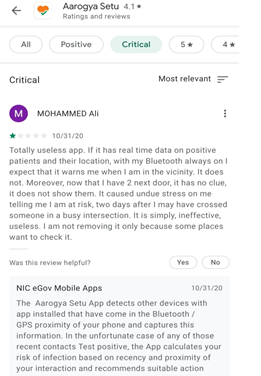

Reviews written by users of the app on the Android Play Store also reflect similar challenges. In a few reviews, users mentioned that the app continued to show them as positive days after they had tested negative. Since the app reviews cannot be verified, they cannot be seen as conclusive evidence. But it is noteworthy that several users seem to report similar issues, as well as feeling anxious as a result of the inaccurate information provided to them by the app. A sample of the most upvoted comments on the version of the app in use in November 2020 is shown below:

Figure 3. Screenshot of most upvoted positive comment (November 2020)

Figure 4. Screenshot of most upvoted negative comment (November 2020)

Despite these various concerns and acknowledgement of the issue by the Volunteers, a clause in the app’s Terms of Service absolves the government from liability.149 Clause (6) states: “The Government of India will make best efforts to ensure that the App and the Services perform as described but will not be liable for (a) the failure of the App or the Services to accurately identify persons in your proximity who have tested positive to Covid-19; (b) the accuracy of the information provided by the App or the Services as to whether the persons you have come in contact with in fact been [sic] infected by Covid-19.”