The Making of Political Ads: Classification as Distraction

A report by

Guest Author

Abstract

Internet based advertising has changed both the Internet and advertising. Efforts to understand the impacts of advertising business models rely on a distinction between ads that might be considered political and the rest. Such a classification empowers platforms to hide from scrutiny a whole lot of ads that are a basic part of an intrinsically political corpus of public discourse. Therefore, enhanced transparency for political ads, rather than shining a light, functions as a cover, obfuscating the impact of targeted and optimised ad infrastructures. In this essay, we use data collected at the Persuasion Lab (ad.watch) to problematise this central classification, and argue that the very nature of targeted ads is inherently political.

[This piece is written by Manuel Beltrán and Nayantara Ranganathan]

In recent years, advertising hasn’t simply been about selling products and the enterprise of political persuasion, it has also led to the privatisation of the agora of public discourse.

In the data we collect and release at the Persuasion Lab, we find that beyond traditional political parties, NGOs use Facebook ads for soliciting donations, activist groups use it for coordinating emergency response efforts around the pandemic, governments use the reach of ads to communicate public service announcements, and public health departments share guidelines in ads. All of that while the platforms take large sums of money for all these communications. It makes one wonder whether we are still discussing ads or whether this merits a more appropriate language and reckoning.

At the centre of the debates on the impact of advertising for democracy remains a tentative distinction that separates ‘political’ advertisements from the rest. This category of political advertisements determines which ads would have to be subject to greater scrutiny, and equally importantly, which actors would have to be more transparent. This classification therefore also props up the idea that an entire class of advertisements is not relevant for understanding how people’s opinions are shaped and worldviews formed.

Social media platforms and the myth of ‘political ads’ #

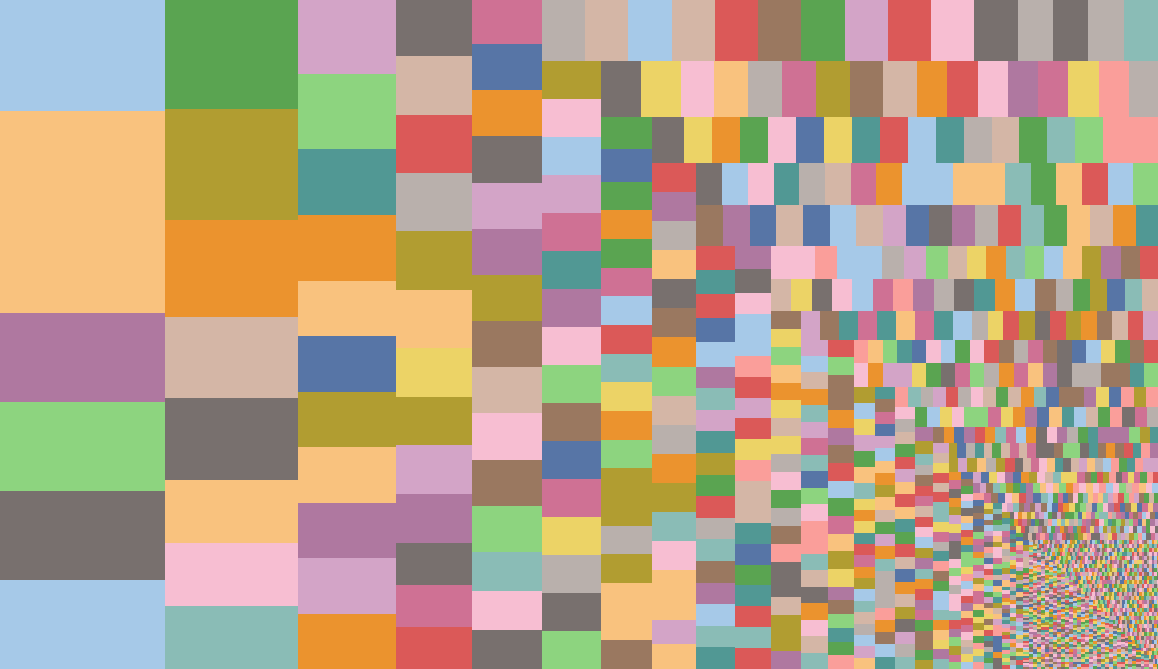

In this interface, browse the actors whose ads Facebook tags as ‘relating to social issues, elections or politics’ that were delivered to India between 1 Jan 2020 and 25 June 2020. The larger the size of the rectangles, the more political ads have been created by the page. Hover over the rectangles to see the number of ads, as well as parts of the contents of the most prominent ad by the page. Use the menu on the right hand side to view ads of selected actors. You can find several instances where by Facebook’s own logic the ads might have easily been excluded. For example, if you check the box to select just “Magicbricks”, you will find that the page is selling property with an in-house gym and swimming pool. Similarly, Cash360 is offering personal cash loan upto Rs. 1,00,000, CarbonKraft is advertising “urban trash management” in which weight and level of waste can be remotely monitored and managed and LEX-STAR LUXURY is selling luxury cars and watches. For more such interfaces, visit ad.watch

Political advertising is an inherited classification from older forms of advertising media. Its continued relevance especially within platforms that deliver posts and advertisements through algorithmic determinations is questionable, and sustained in the interest of the platforms’ business models. In other words, if propaganda is understood as information with an agenda1, then all circulation and delivery of information driven by algorithmic systems are, by their very nature, agenda-driven and propagandic. The circulation is always political.

Even platforms having seemingly oppositional approaches like Twitter (which bans political ads) and Facebook (which provides special privileges to political ads) nevertheless agree and support the notion that the category of political ads is a relevant and useful way to sort advertisements.

One of the most resonant statements emerging from feminist movements in the 20th century has been ‘the personal is political’. The title of an essay written by Carol Hanisch in 1969, and conceptualised by her editors, this war-cry was meant to shift what was commonly constructed as the contents of the political realm. It is not just matters of the state, matters of governance, to which only a certain section of the population have access, but also the personal realm of what happens in the home, of what happens in interpersonal relationships. Explaining the term, Hanisch says in a 2006 introduction to her 1969 essay: “ ‘political’ was used here in the broad sense of the word as having to do with power relationships, not the narrow sense of electoral politics.“2 But as we see in the table above, platforms across the board have created a glass ceiling for what we might consider as political.

Is business political? #

According to FACEBOOK Inc., at the heart of the classification between political ads and the rest, is the question of whether or not the ad is a call for commerce, or a call for advocacy.

Social media companies offer a wide array of utility for advertisers: from promising store visits and conversion into sales to ensuring traffic, app installs, lead generation, etc. Advertisements are thus no longer simply about closing a sale. Even the simple fact of watching a video or clicking a page are quantifiable steps that pay off for advertisers.

So what, according to FACEBOOK Inc., are political ads? Ads by political parties and campaigns, candidates running for elections easily qualify as political. The disturbances to a clean classification of political ads from the rest is visible within the category of ‘issue ads’. In a way, one could think that this category is a container of anxieties of classification, holding those issues which beyond a measure of doubt qualify as political, even when they are not sold by politicians. This subclass constitutes ads advocating for different issues even when they are not created by politicians.

Facebook explains what it considers as issue ads or social issues3:

Social issues are sensitive topics that are heavily debated, may influence the outcome of an election or result in/relate to existing or proposed legislation. We require increased authenticity and transparency to run social issue ads that seek to influence public opinion through discussion, debate or advocacy for or against important topics, such as health and civil and social rights. These ads can come from a range of advertisers. They include activists, brands, non-profit groups and political organisations, who are all required to be authorised and use “Paid for by” disclaimers on ads that take a stand on issues within our policy.

And conveniently for Facebook, the contents of social issues can change at their own whims.

We regularly review our Advertising Policies and update them when needed. As a result, these lists can change over time.

Until sometime ago, ‘crime’ made it to the list of social issues in the European Union, but not in Canada. ‘Environmental politics’ was a political issue in Canada and the European Union but not in Singapore. ‘Guns’ still form part of the list of social issues in the United States but not in Taiwan or the United Kingdom.

The items on these lists that delineate the political from the rest have a significant import. For example, an ad about abortion may be classified as political in the United States, where both pro-abortion groups like Planned Parenthood as well as anti-abortion groups run ads advocating for their positions. Since it is topical in the US and a matter of national debate, where national debate means that political candidates are pressured to have views on the matter, abortion ads are considered political. While Facebook used to list abortion under the issues in the US, it has disappeared in later iterations.

Regardless of what this update in policy means, one can find many ads related to abortion that are labelled as related to ‘social issues, elections or politics’ in the data. Consider countries like Ireland, where abortion is restricted and regulated, or Argentina, where abortion is a crime that is punishable with prison time. The scrutiny about such ads depends on whether, in Facebook’s everchanging wisdom, ads about abortion will be classified as political or not. On the other hand, if Facebook decides to classify abortion as political in a country where the issue is already settled, then it could serve the function of increasing political currency of an issue that is no longer controversial.

A brief look at the actors whose ads are classified as political reveals a motley crew: government departments, aspiring electoral candidates, political parties and so on. But a closer look reveals that ads by many corporates, businesses, lobbyists, influencers and individuals also fall within this category.

Politics of classification in big infrastructures #

Classification schemes adopted by big data infrastructures like Facebook find their way into legislation, popular imagination and public debate. The productive nature of language and sorting processes is used to sanctify these classifications and apply the classifying party’s outlook to all participating entities.

As infrastructure studies scholars Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey Bowker remind us, anthropologists have long studied classification ‘as a device for understanding the cultures of others.’4 If there is a culture perpetuated by social media companies like Facebook, which have largely risen to be global monopolies operating in the absence of regulatory sanction, then their ways of classification of data is central to understanding the cultures they perpetuate. This might be at the level of how they classify their data as much as the architecture of their office spaces or their hiring practices. Classification are ‘artifacts embodying moral and aesthetic choices that in turn craft people’s identities, aspirations, and dignity.‘5

On the one hand, companies like Facebook have always recognised the import of categories, especially as it relates to the obligation categories place on the platforms. It took much advocacy on the part of anti-caste activists to bring Facebook to include the category of ‘caste’ within its list of reasons of why posts may be reported as hateful. But elsewhere, classification stands separated from its political import.

What is the singular message perpetuated by the advertisement classification policy as it stands? It is that anything in the name of an economic transaction lies outside the ambit of the political. A recent update to Facebook’s policies makes this distinction between economic activity and political activity sharper than ever. According to this update, an ad that states ‘We need gun reform’ would need authorisation and a disclaimer to run in the United States, while an ad that says ‘Attend a course on gun safety starting September 1’ would not need any frills of authorisation or disclaimer required of political ads. The rationale is that any ad that contains advocacy and debate, like ‘We must fight against widening income inequality in our state’ would need a signifier stating its political nature. But by the same logic, Facebook would exclude from any kind of scrutiny an ad that would state ‘Come to our job fair tomorrow! Doors open at 8am.’

This is simplistic at so many different levels. Classification is a way of seeing, and allows us to visibilise different ways of looking at the data. Almost inescapably, it also invisibilises other ways. The choice is an ethical as well as material one. In the case of platforms, the classification of ads is entirely focussed on sorting the ads on the basis of their content or on the basis of the advertiser’s character. The data being invisibilised here is the circulation dynamics, which when considered, arguably makes all ads necessarily political, as targeting choices allow for inclusion and exclusion on the basis of race, class, gender, etc.

A useful definition of classification is one forwarded by Leigh Star and Bowker in Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. They propose that ‘a classification is a spatial, temporal, or spatial-temporal segmentation of the world. A “classification system” is a set of boxes (metaphorical or literal) into which things can be put to then do some kind of work — bureaucratic or knowledge production.‘6 Indeed, the classification being instituted by platforms is not inconsequential. By adapting these classifications in laws and regulation without a critical assessment, these instruments, supposedly meant to counteract the harms from advertising phenomena, inadvertently perform the role of standardisation of these classifications, ossifying business logics into our ways of meaning-making.

Another problem of classification, and its consequences, is visible in how Facebook treats gender classification for users and for advertisers. On the front-end, Facebook allows users to self-select their gender identification from a variety of options, including an invitation to describe in their own words, outside of the categories offered. However, when advertisers are given preferences for targeting their ads, the classifications available are merely male and female. Not only does this reveal how Facebook presents the gender binary to one set of use-cases while putting on a politically-progressive façade for users, it suggests that Facebook categorises people into the gender binary even when they might have self-identified otherwise.

Outsourcing the labour of classification #

Classification functions of Facebook are done partly by advertisers self-declaring their ads as political and partly through algorithmic means, where Facebook spots advertisements running without disclaimers but falling within the category of political ads. However, a third way of classification is something which has not been formalised by Facebook as a method, but which very much operates as a safety net for Facebook’s errors: Facebook relies on users to flag ads when they are political but are not seen with necessary disclaimers.

Top Facebook executives spend a good amount of time encouraging users to flag problematic advertisements, demanding them to perform free labour of classification. Instead of structurally addressing the problems themselves, Facebook manages to divert responsibility, position their ads oversight process as a success, and ultimately sustain existing classifications as viable.

Facebook’s forthcomingness in the classification process, the resources the platform is willing to dedicate and its impacts are clear to see. Countries which have verification procedures in place and a degree of enforcement by Facebook account for more than 95% of the data available on political advertisements. But 160 countries in the world account for only 5% of the data available.

The complications and messiness of classification might make one surmise that platforms like Facebook are damned if they do and damned if they don’t. However, the finer point to be gleaned comes forth in considering exactly whose interests these classifications are working to serve. If such classification is questionable at best, and disingenuous at worst, why do platforms nevertheless work with this imperfect fiction? The answer might lie in the fact that classification serves an important purpose for social media platforms: of insulating questions about the political economy of these platforms, and focusing concerns about the political to a narrow enterprise of parsing the content of the ads. In a world of personalised ads delivery, the question of why any ad is delivered to the chosen persons is itself a highly politically charged and materially negotiated question.

This work is supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation.

Released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

-

Renée DiResta, Computational Propaganda, The Yale Review, https://yalereview.yale.edu/computational-propaganda ↩︎

-

Carol Hanisch, The Personal Is Political, January 2006, page 1, Available at https://webhome.cs.uvic.ca/~mserra/AttachedFiles/PersonalPolitical.pdf ↩︎

-

FACEBOOK Inc. Business Help Centre, Available at https://www.facebook.com/business/help/214754279118974?id=288762101909005 ↩︎

-

Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star, Sorting Things Out, Classification and its Consequences, MIT Press, 2000, page 3 ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid., page 10 ↩︎