Tech Tools to Facilitate and Manage Consent: Panacea or Predicament? A Feminist Perspective

A report by

Tripti Jain

in

Data

Abstract

In this exploratory study, I assess account aggregators (AA) in India, and the emerging ecosystem in which they are embedded, against the feminist principles of consent in the age of embodied data. While consent continues to be a cornerstone of ensuring autonomy across data protection regimes, research has nevertheless been critical of it. In an earlier study, Anja Kovacs and I (Kovacs & Jain, 2020) identified the current perception of data, i.e. as a resource, as one of the crucial problems plaguing existing consent regimes; instead, we demonstrated, data is increasingly functioning as an extension of, or even integral to our bodies. We then built on this reconceptualisation to draw parallels between feminist learnings around sexual consent and data protection, to delineate six feminist principles that need to be observed in data protection regimes for consent to be meaningful there (Kovacs & Jain, 2020). Meanwhile, technology-enabled consent frameworks, such as the account aggregator framework conceptualised and launched in India, aim to similarly address key criticisms of consent regimes today, to thus strengthen user consent and the autonomy of individuals. I examine in this research study how well the developing AA ecosystem in India is delivering on these claims in practice. Assessing it against each of the feminist principles of consent, I ask to what extent AAs align with the feminist principles, whether AAs are effective, and what the way forward is. As we will see, while AAs do mark a notable improvement over existing consent regimes in a number of ways, many weaknesses remain. All too often, this is because AAs are positioned as a silver bullet: changes in the broader landscape in which they are embedded, while crucial to their mission, remain absent. As long as this does not change, it will not be possible for AAs to do all the work that is currently expected from them.

Introduction #

In this exploratory study, I assess account aggregators (AA) in India, and the emerging ecosystem in which they are embedded, against the feminist principles of consent in the age of embodied data. Account aggregators have been developed with the stated aim of improving consent management by users and thus enabling greater user autonomy while expanding participation in the digital world. Through this assessment, I aim to understand to what extent this developing ecosystem currently delivers on these claims in practice, where there might be room for improvement, and what such improvements would look like.

Context #

Most data protection frameworks across the globe consider consent mechanisms as tools for privacy self-management (Solove, 2013) and enablers of individual autonomy. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the California Consumer Privacy Act, the United Kingdom’s Data Protection Regulation and India’s Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 all recognise “consent” as an expression of agreement, or denial of agreement, on the part of the user to share their data and to allow for its accumulation and processing. It is “consent” that effectuates the formal social contract (Kaye et al., 2015) between data subjects and data fiduciaries.

Despite the centrality of consent, research in the past has, however, been critical of consent mechanisms. (Kovacs & Jain, 2020) Some scholars, such as Matthan (2017), have therefore suggested moving away from consent and exploring other realms of ensuring privacy, such as accountability, instead. However, in earlier research Anja Kovacs and I (Kovacs & Jain, 2020) have argued that consent mechanisms can be rescued. While consent regimes may fail to enable the autonomy of individual users for a range of reasons, what unites them, we demonstrated, is that they are based on the conceptualisation of data as a resource. This perception of data sometimes invisiblises and at other times allows us to overlook the harms that are caused to human bodies by decisions that are made on the basis of individual’s data. For example, individuals have been denied access to rations, which they have a right to under Indian law, because of fingerprint authentication failures (Khera, 2019). Rather than simply a resource, data is, in other words, increasingly an extension, or even integral to our bodies, and recognising this allows us to also recognise more easily the range of harms incurred on bodies as a result of different data driven exercises. Having established the close connections between bodies and data, Kovacs and I turned to existing areas of research in which questions of consent and the body have figured strongly for guidance on how to strengthen consent regimes, and found that feminist debates on sexual consent have particularly rich discussions on consent and body. Based on a detailed examination of these debates, we, finally, formulated a list of six core principles that take the integrity of the self as their starting point and that need to be observed in data protection regimes for consent to be meaningful there as well (Kovacs & Jain, 2020).

We are not the only ones who continue to recognise the value of consent, however. Among particularly interesting other efforts are several concrete technology-enabled tools and frameworks that have been proposed to enable consent and are being launched in India and across the globe. In India, these tools and frameworks include the Electronic Consent Framework by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) by iSPIRT and NITI Aayog (a think tank of the Government of India), and the Account Aggregator Framework by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). Among examples elsewhere are the Open Banking System in the United Kingdom and the X‑Road framework in Sweden. All these tools or frameworks claim to enable individuals to exercise greater control over their data by allowing them to manage their consent more efficiently. They aim to do so by addressing some of the common criticisms that the consent régime faces, including consent fatigue, the complexity of notice, and that consent is often sought up-front for subsequent transactions (Basu & Sonkar, 2020). All these, and others, are concerns that Kovacs and I addressed by means of the feminist principles of consent as well (Kovacs & Jain, 2020).

In order to understand how well such technology tools deliver on their promises, I aim to assess, in this exploratory study, the efficacy of one such proposed technology solution, the account aggregator, against the feminist principles of consent delineated by Kovacs and Jain (2020). In doing so, I aim to understand to what extent AAs align with the feminist principles; whether they are effective in strengthening user consent; and what can be done additionally to further strengthen the consent mechanism in the AA framework. The paper focuses on the account aggregator framework in particular, as the other Indian frameworks that have been proposed are either a component of the AA framework or are yet to manifest into working tools and technologies. On the other hand, the account aggregator framework, which was proposed in late 2015, has seen significant progress. In fact, Onemoney, one of the AAs, has already launched its beta application, thereby making this ecosystem a suitable fit for this exercise.1

Research Methodology #

To answer the research question, a mixed-methods approach was adopted. First, I mapped all provisions in Indian statutes and directions that specifically concern consent management tools. Then I searched through the websites of the account aggregators, their beta applications, their privacy policies and terms of use, and other documents. I did so to understand the vision behind the introduction of the account aggregator framework, how it is being adopted, and its impact on individuals’ privacy and autonomy. Due to the nascent nature of the technology, the literature available in the public domain was, however, limited, which served as a hurdle for this research.

I tried to fill any gaps through interviews with early adopters of the ecosystem, to the extent possible. However, it deserves to be pointed out that some concerns can only be clarified as the ecosystem evolves. I conducted semi-structured interviews with eleven key informants who have been involved in envisioning, designing, adopting and critiquing this ecosystem. I interviewed them for their expertise on the subject matter or due to their extensive contribution to building digital public goods. These interviews were conducted on telephone or online (mobility constraints imposed by the nation-wide COVID-19 lockdown made in-person interviews not possible). The interviews took place between November 2020 and January 2021 in English and Hindi. The following are the persons that I interviewed for this research: A Krishna Prasad (Founder of Onemoney, the first account aggregator to get an operating license and the first AA to launch its beta application), B.G Mahesh (Co-founder of Sahamati Foundation, a self-regulatory organisation for the AA framework), Kamya Chandra (building public digital platforms to drive India’s economic growth at iSPIRT Foundation and co-author of the DEPA Book), Malavika Raghavan (Senior Fellow for India, Future of Privacy Forum), Munish Bhatia (Co-founder of Finvu, an AA), Praneeth Bodduluri (Co-founder, Base Account), Rahul Matthan (Partner at Trilegal), Saurabh Punjwani (Volunteer Technologist at iSPIRT Foundation and one of the security engineers involved in conceptualisation of the AA ecosystem), Srikanth L (Public Interest Technologist, with expertise in digital payments), and Vinay Sathyanarayana (Chief Engineer at Perfios Software Solutions Pvt. Ltd, an AA). Names have been used after seeking explicit written or verbal consent from the research participants.

Finally, along with the semi-structured interviews, I also conducted a review of the literature regarding the regulatory frameworks governing the AA ecosystem, covering both academic papers and newspaper articles.

As noted, the AA framework is still being developed and iterated. Therefore, some concerns and nuances may remain unarticulated for the moment. However, I hope this research and the questions that I aim to answer herein may provide some useful insights to further strengthen consent management frameworks, at this early stage.

In what follows, I will first outline the landscape of technological tools that claim to operationalise consent in India. In that same section, I will also take a deeper dive into the account aggregator ecosystem and delineate its objectives, major stakeholders and how the consent mechanism in the ecosystem works. The heart of the paper is section three, in which I will outline, for each of the feminist principles, a number of key conditions that need to be fulfilled to enable meaningful consent in the AA ecosystem, then examine and assess the tool against each of these conditions, drawing on the interviews conducted and literature available. In section four, I will then summarise, based on the earlier analysis, to what extent the AA framework complies with the feminist principles. Finally, in section five, I will make some concrete recommendations to address the concerns identified in the paper and thus fully meet the minimum requirements necessary to ensure meaningful consent.

Understanding the Landscape, and Account Aggregators and Their Functioning #

Since 2015, a number of technological tools and frameworks that claim to operationalise consent have been proposed in India. Understanding this landscape, and the place of account aggregators within it is, essential before assessing the account aggregator ecosystem against the feminist principles of consent.

A brief overview of consent enabled technology tools in India #

A number of technological tools and frameworks that claim to operationalise consent have been proposed in India thus far. Some of these tools and frameworks are built on each other’s specifications or have borrowed underlying architecture from one another. However, each of these tools has been introduced in different years, by different entities and with some additional features. Thus, it is imperative to understand these tools separately. A chronological analysis of these consent management tools and the overarching framework suggests that the idea was first mooted within the financial sector through the RBI Master Directions, 2016. Upon operationalising the Master Directions, the regulators seem to have realised the necessity of allowing secure sharing of user data in various sectors, therefore encouraging technical infrastructure that enables more broadly secure collection of user information based on consent provided by said user. The Electronic Consent Framework (MeitY, 2018) intends to achieve this goal. Following this, the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, in section 23, identified and gave legal footing to a new category of entities called “consent managers”. Finally, the draft DEPA Book (NITI Aayog, 2020) was brought out as an umbrella framework to advance consent management systems through technical and regulatory mechanisms. While these frameworks and tools may have emerged in separate years, a deeper dive into each reveals that these different modules were, in fact, in the works parallelly.

Account Aggregators (2016)

In 2015, at the 52nd meeting of the Central Board of the Reserve Bank of India, the Governor announced that the RBI will put in place a regulatory framework to allow a new kind of non-banking finance company (NBFC): account aggregators (Reserve Bank of India, 2015). The conception of account aggregators resulted from the recommendations of the Financial Stability and Development Council. The Council recommended a new kind of NBFC which would help people see their accounts across financial institutions in a common format. Following that, in 2016, the draft Directions regarding Registration and Operations of NBFC – Account Aggregators were issued under section 45-IA of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934.2 These were finalised by 2 September 2016, as the RBI’s final Master Direction — Non-Banking Financial Company — Account Aggregator (Reserve Bank) Directions (henceforth, “the Master Directions”).3 Along with these regulatory requirements, the RBI also issued, in 2019, the Technical Specifications for Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to be used by all participants of the account aggregator ecosystem.4

In 2018, after the release of the Master Directions, the RBI invited applications from non-banking financial companies to be licensed as account aggregators (NBFC-AAs). Currently, there are six entities that have been given in-principle and operating account aggregator licenses from the RBI. The first license for an NBFC-AA was issued in 2018 (Lakshmanan, 2018). In 2019, Sahamati, a non-profit collective of AAs was formulated. It is similar to the Wifi Alliance, the GSM Alliance, the Bluetooth Alliance, and other such entities, in that it acts as a self-regulating organisation. Sahamati specifically aims to work towards growing the adoption of the AA framework in the financial world, which it claims will achieve the goal of “data empowerment” for data principals.

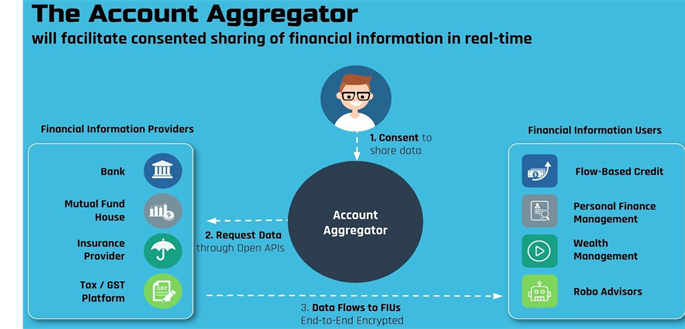

Account aggregators consolidate the financial data of an individual, previously spread across various financial sector institutions, and facilitate access to such financial data by acting as “consent brokers”: entities mediating consensual data transfer across financial entities, such as banks and mutual fund companies, termed financial information users (FIUs). It is claimed that account aggregators will make credit accessible to the people who are currently not part of the credit ecosystem, thus ensuring the formal financial system becomes more inclusive (Belgavi & Narang, 2019).

As per the existing RBI Master Directions, 2016, AAs are currently only allowed to serve as a data pipe for financial data. However, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) Chairman RS Sharma, in August 2020, argued that telecom service providers should be allowed to be financial information providers as well. This example indicates that there exists scope to extend the use cases and information providers within the AA ecosystem.

Electronic Consent Framework (2018)

The Electronic Consent Framework (MeitY, 2018) was proposed by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology to enable the effective and secure implementation of two government policies: the Policy on Open Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) for the Government of India,5 and the National Data Sharing and Accessibility Policy (NDSAP), 20126. Both policies focus on laying down guiding principles for data sharing. The Open APIs Policy was formulated to promote software interoperability for all e‑governance applications and systems. It aims to enable any public service provider to access data and services so as to promote participation of all stakeholders, including citizens. The NDSAP delineates an overarching framework for sharing of data that is collected by State entities using public funds with service providers that work for public interest. Embodying the guiding principles prescribed by the Open API policy and the NDSAP, the Electronic Consent Framework was drafted. It is a framework that runs on an Open API and allows data subjects to entrust a platform with sharing their personal data with other data fiduciaries on a need basis, while providing technical safeguards for the use and management of consent in a paperless ecosystem.

Consent Manager (2019)

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 borrowed underlying principles from the discussions around DEPA (see below) and the Electronic Consent Framework, and proposed, in section 23, another tool: the consent manager, a data fiduciary that enables a data principal to gain, withdraw, review and manage their consent through an accessible, transparent and interoperable platform. However, the current version of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 is silent on the technical, operational, financial and other working conditions of the consent manager. It states that these specifications will be delineated in regulations. Thus, it is unclear for the moment how these consent managers will function, and whose interests they will serve and to what extent.

Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) (2020)

The Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) (NITI Aayog, 2020) is the consent layer of Indiastack,7 developed by iSPIRT and NITI Aayog (a think tank of the Indian government). It is one of the frameworks proposed in the Indian context to empower individuals to control how their data is being used. In fact, the work on DEPA seems to have predated the idea of consent managers in the Personal Data Protection Bill. The ball started rolling as early as August 2017 (ProductNation/iSPIRT, 2017a) and has since been championed by iSPIRT.8 DEPA is not just a technology tool but a sector-agnostic overarching framework that governs the consensual transfer of user data currently resting in silos. The proposers of the DEPA framework are of the view that digital footprints can serve as a means to build trust between the users and institutions (NITI Aayog, 2020, p. 25), and that empowering individuals with control over their data will enable their well-being and allow them more autonomy over their personhood. To ensure this, DEPA proposes to enable consensual sharing between service providers of personal data that currently resides in silos, so as to allow users to access better financial, healthcare and other socio-economically important services in a secure and privacy-preserving manner. The architecture is built with the expectation that, for example, a bank could design and offer regular big and small loans based on demonstrated ability to repay (known as flow-based lending) rather than only offering bank loans backed by assets or collateral. The decision to offer the loan would hinge on the integration of financial data such as GST (Goods and Services Tax) payments, payment of invoices, etc., which can help demonstrate the ability to repay.

Concretely, the DEPA framework proposes the development of new market entities or institutions, known as consent managers, to manage consent. Consent managers in the financial ecosystem are known as account aggregators, which we have already discussed above. Policymakers argue that this new class of institutions, i.e. consent managers, will be able to ensure individuals’ data rights around privacy and portability because, unlike current data fiduciaries, who are interested in collecting behavioural surplus of users, these will be incentivised to protect user interest without engaging in exploitative practices. (NITI Aayog, 2020). They argue this on the basis that these new market entities have their economic incentives aligned with those of the users regarding the sharing of personal data, as they can charge a nominal fee to facilitate data exchange (NITI Aayog, 2020). Currently, the financial model proposed for account aggregators, for example, is based on charging the FIU or the end consumer, but not the FIP (financial information provider), for the data requested (Sahamati, 2019a).

The DEPA Book recognises the following three “digital public goods” as basic building blocks that will govern DEPA’s technology architecture: 1. MeitY’s Electronic Consent Framework — to build consent artefacts;9 2. Data sharing API standards — to enable an encrypted flow of data between data providers and information users; and 3. sector specific data information standards10 (NITI Aayog, 2020 pp.38).

Implementation of the DEPA framework has already started in the financial sector, with the launch of the account aggregators (AAs), under the joint leadership of the Ministry of Finance, the Reserve Bank of India, the Pension Fund Regulatory & Development Authority (PFRDA), the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA), and the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). AAs are discussed at length in the next section of this paper.

The architecture was also expected to be piloted in the health sector in 2020; however it has not yet been launched at the time of writing. On 15 August 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the National Digital Health Mission, which includes a Health ID and a data-sharing framework for personal health records. This is based on the National Digital Health Blueprint (Ministry of Health, 2019), published by the Ministry of Health, which in turn builds on the National Health Stack Strategy Paper, published by NITI Aayog in July 2018 (NITI Aayog, 2018).

Following the TRAI consultation report on privacy (TRAI, 2018), released in July 2018, and a workshop held by TRAI Chairperson RS Sharma in August 2020, it is expected that DEPA will also be launched in the Telecom sector (NITI Aayog, 2020 p. 48). RS Sharma highlighted that in India, telecom data often constitute the first digital footprint of a low-income household. Therefore, a steady history of on-time recharges could formulate a basis for credit history. Telecom service providers could, thus, serve as information providers as well.

Account Aggregators and Their Functioning #

Before I begin to assess the consent mechanism in the AA framework from a feminist perspective, it is further imperative to learn what the AA ecosystem aims to achieve, who the key stakeholders are in the ecosystem and how they are expected to interact within it, as well as to better understand how consent functions in the ecosystem. In this subsection, I outline each of these aspects.

Objectives of Account Aggregator Framework #

As noted earlier, policymakers and early adopters of the AA ecosystem observed that currently, financial data of individuals rests in silos, and even if an individual wishes to access their own financial data in consolidated form, there exists no platform that allows individuals to do so (Sahamati, 2019b). Similarly, if someone is required to transfer their data to other entities, there are no digital means available to do so. In times of increasing datafication of people’s bodies and lives, spearheaded by private entities, this has resulted in reduced autonomy of an individual in decision-making. Thus, to enable easy viewing and sharing of financial data with consent, AAs were conceptualised.

Moreover, good connectivity to the formal financial system ensures access to a wide range of financial products. The AA framework assists in decision making required by financial institutions for the provision of financial services such as (lending, wealth management and personal finance management, by eliminating paper trails.11 Thus, AAs can facilitate access to financial services and credit for earlier underserved and unserved segments, i.e. enable financial inclusion, by reducing information asymmetry. .

In the first press release by the RBI that touched upon AAs (Reserve Bank of India, 2015), the policymakers envisioned AAs as NBFCs that would merely enable users to see their financial data spread across different financial institutions. However, in the final Master Directions from the RBI, a transformation was observed in the role of account aggregators. According to the 2016 Directions, AAs were conceptualised to help end-users keep oversight of their personal data by managing consent and subsequently the flow of information between the various financial institutions with which they engage in data-generating exchanges.

Key Stakeholders in the AA Ecosystem #

There are 4 major actors in this ecosystem: FIPs, FIUs, end-users, and the AAs themselves.

FIPs (Financial Information Providers): As the name suggests, financial information providers are the data fiduciaries that will be providing information to other financial entities, enabling them, in turn, to provide financial instruments to the customer. FIPs could be entities like banks, banking companies, non-banking financial companies, asset management companies, depositories, depository participants, insurance companies, insurance repositories, pension funds and such other entities as may be identified from time to time by the RBI for the purposes mentioned in the RBI directions 2016. So far a total of eleven institutions have publicly expressed their participation in the ecosystem as FIPs. They are Axis Bank, Bajaj Finserv, DMI Finance, Federal Bank, HDFC Bank, Hero FinCorp, ICICI Bank, IDFC FIRST Bank, Indusind Bank, LendingKart, and State Bank of India (SBI).

FIUs (Financial Information Users): Financial information users are data fiduciaries that seek information from FIPs to provide financial services. FIUs are entities registered with and regulated by any financial sector. They could very well be FIPs themselves, such as banks, asset management companies, and insurance companies. For example, a bank might require certain financial data prior to issuing a credit card to an individual; as it accesses data through the pipeline mediated by AAs, it will then be acting as an FIU.

Account Aggregators (AAs): AAs are non-banking financial companies, defined and regulated by the central bank, i.e. the RBI. No other entity apart from an NBFC can seek a license to be an AA. AAs are consent managers in the financial sector. The RBI has confirmed in-principle approval of six account aggregators for building a data-sharing solution: CAMS FinServ, Cookiejar Technologies (product named Finvu), FinSec AA Solutions Private (product named OneMoney), National E‑Governance Services Limited (NESL Asset Data Limited), Yodlee Finsoft, and Perfios Account Aggregation Services (Sahamati, 2020a).

End-users or Customers: The end-users enter into a contractual arrangement with the account aggregator to avail of their services.

Obtaining Consent in AA Framework #

On the basis of the information available about AAs (Reserve Bank of India, 2016b; Sahamati 2019a), I have been able to piece together how AAs function, and how they enable FIPs and FIUs to join hands. AAs are data blind pipelines at the best of the end user. This means that data will be encrypted and access will be only available to those who have private keys to the encrypted data. Let us trace the user journey here to understand in more detail how the consent mechanism works.

A user may access the AA’s services through an app made available by the AA on smartphone app stores or through the AA’s website. Users may sign up on the AA app with the usual credentials. Currently, only full names and mobile phone numbers are being used as identifiers. We are yet to see whether and which other identifiers will be required as the system evolves, such as PAN or Aadhaar Number. This is critical as this might contribute to function creep and other harms to user privacy.

Once signed up, the user should link all their financial accounts and instruments which they wish to manage through the AA, such as bank accounts, demat accounts, fixed deposits, etc. In order to link their financial accounts and instruments with the AA, users are required to furnish the mobile number through which they have already registered with the FIPs. The AA then looks up the registered mobile number across various FIPs and provides the user with a list of accounts and instruments that are linked to their registered number, and allows the user to choose the account(s) or instrument(s) they wish to link. Once the bank accounts and instruments are linked, users can start managing their consent concerning their data for the linked accounts and instruments.

At the moment, the AA ecosystem envisions four types of consent:

a. View: allows FIU to only view the data;

b. Store: allows FIU to store the static data unless the consent expires;

c. Query: allows FIU merely to authenticate the veracity of the data that user has provided;

d. Stream: gives FIU access to the flow of data, such as ongoing transactions, etc., unless the consent expires.

Along with different types of consent, the ecosystem also envisages two types of fetch:12

a. One time: wherein FIUs seek all the desired information in one go;

b. Periodic: which enables FIUs to seek information in a periodic manner, such as on a daily, weekly or monthly basis.

From their side, FIUs can raise a consent request through the AA to seek information from the user. As per the RBI Master Directions 2016, this consent request is required to have the following details:

● the identity of the customer and optional contact information;

● the nature of the financial information requested;

● the purpose of collecting such information;

● the identity of the recipients of the information, if any;

● the URL (in case of website access) or other address to which notification needs to be sent every time the consent artefact is used to access information;

● the consent creation date, expiry date, identity and signature/digital signature of the account aggregator; and

● any other attribute as may be prescribed by the RBI.

Users can give or deny consent to the FIU for the request raised. Once the request is accepted by the user, the AA conveys such consent to the concerned FIP(s). The FIP(s) would then create a private key to encrypt the data requested and send it across to the FIU through the AA. In order to decrypt this information, the FIU creates a public key which goes all the way to the FIP, which then, after receiving consent, encrypts the desired information and sends it across to the FIU.

Figure 1. Consent Flow in the AA Framework (Sahamati, 2019a)

Examining the AA Ecosystem against the Feminist Principles of Consent in the Age of Embodied Data #

In the previous sections of this paper, we learnt about the reasons for the introduction of the AA ecosystem and the need to assess the AA ecosystem. In this section, the efficacy of this framework will be examined against the feminist principles of consent in the age of embodied data proposed by Kovacs and myself (Kovacs & Jain, 2020). To do so, first, let’s recall the feminist principles:

● Consent must be embedded in a notion of relational, rather than individual, autonomy.

● Consent must be given proactively, communicated in the affirmative.

● Consent must be specific, continuous and ongoing, to be sought for different acts and at different stages. Consent is required to be built.

● Consent is a process, and thus opens up a conversation, rather than entailing merely a yes/no decision.

● Consent allows for negotiation by all parties involved.

● Conditions must be created so that consent can be given freely. This implies that the person should be free from any fear of oppression or violence of any kind.

To examine the ecosystem against the deduced consent principles, it is imperative to understand the conditions necessary to enable a consent principle. It is impossible to present in detail all the conditions to enable a principle, their nuances and what all could they entail — nor do I want to claim that I possess full knowledge of all changes that are needed at this time. The framework is still being developed, implemented and iterated, and in the middle of this process, I can only propose qualifiers and conditions based on what is known about the ecosystem now. Nevertheless, on the basis of existing literature, I have identified a number of such key conditions for each principle, and will assess the AAs and their functioning against this.

To conduct this exercise, I follow the same procedure for each principle. I first lay down the principle and illustrate its importance. Then I highlight its relevance in the AA ecosystem. After doing so, I identify the conditions to enable a principle, based on what is known about the ecosystem so far, and examine the ecosystem against these. A summary of all principles and their conditions can be found in Annexe I.

Consent must be embedded in a notion of relational, rather than individual, autonomy #

THE PRINCIPLE: Feminists such as Lacey (1998), and Nedelskey (1989) have noted that the assumption that every individual is free and autonomous in every context is false. Individual autonomy cannot be presupposed. Instead, autonomy is always relational: it is conditional on multiple factors concerning the individual (Nedelsky 1989, p. 12). Thus, a person can express autonomous consent only if the conditions allow them to do so, because irrespective of how robust their personal intentions are, external conditions can nevertheless prevent them from expressing autonomy.

RELEVANCE: For the data governance régime, too, this means that when consent is sought, the nature and quality of this consent is determined by the conditions under which this consent is obtained. This understanding is a departure from the existing paradigm, in which consent is so individualised that it ignores the conditions and mechanisms that have been deployed to seek consent online (Cohen, 2019).

In fact, scholars such as Austin (2014) and Cohen (2019) have highlighted that the reason for the current failure of notice and consent mechanisms in data governance is precisely that they overlook the full complexity of social conditions. For example, current notice and consent mechanisms are based on the assumption that an individual has an ability to exercise autonomy by expressing consent on the basis of the notice furnished. However, the following conditions are often not accounted for: the ability of an individual to assess a notice, the contradictory interests of the parties involved (i.e. data fiduciaries and data subjects) while collecting data, legalese used in notices, etc. As a result, the individual from whom consent is sought is often unaware of many of the risks and harms, thereby making consent meaningless. Thus, there’s a need to move away from a “subject-centered to a condition centric approach” (Cohen, 2019 p. 17).

As discussed above, account aggregators are tools that aim to empower the people in India with the ability to manage their financial data in a convenient, secure and transparent manner. In order to do so, it provides for a consent artefact that empowers individuals to regulate access to and manage their financial data according to their will. As observed above, to ensure autonomy and enable individuals to exercise their will in practice, it is pertinent to ensure that a condition centric approach is deployed. Thus, AAs must approach consent in a relational manner and not just in an individual manner.

ASSESSMENT: What does this mean in practice? Let us consider four key conditions that need to be in place to strengthen user’s relational autonomy, and examine whether they are being observed by the current framework.

The ecosystem should provide means that prevent data fiduciaries from misappropriating and misusing user data

Currently, the ecosystem only prevents AAs from misappropriating and misusing user data. The Master Directions, 2016 state that the AAs are data blind. This means that the data that flows through AAs is encrypted and AAs cannot access or use it. In addition, the Master Directions lay down restrictions to prevent misuse of data by AAs. Among other duties, this includes a prohibition on retention and disclosure of user information by the AAs in the absence of explicit user consent.

However, the threat of misuse of personal data continues to persist in the ecosystem because FIPs and FIUs are only lightly regulated as far as privacy of user data is concerned. Direction 7.6.2 of the Master Directions provides that the information received by an FIU through an AA cannot be used for any other purpose except as is specified in the consent artefact. However, there is no technology layer or regulatory method to assess how FIUs are using the personal and financial information that they receive. Apart from this one measure, the Master Directions, 2016 put the onus on sectoral regulators — such as those from IRDA and SEBI — to regulate either end of the data blind pipes (i.e. FIPs and FIUs) with respect to data, audits and accountability, among other things. Laws that currently govern data practices in the banking sector include section 43A of the Information Technology Act, 2000; the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011; section 3 of Public Financial Institution Act, 1983; and section 29 of the Credit Information Companies Act, 2005. However, these laws are dated and cannot address the problems posed by existing data practices and technology, such as overcollection of personal data, creation of profiles and serving of targeted advertisements. A public interest litigation was filed at the Delhi High Court seeking a ban on the sharing of PAN and financial transaction data of clients with credit rating agencies without clients’ formal consent (PTI, 2019). This further highlights that FIPs such as CIBIL, Equifax and other credit rating agencies, in particular, are under-regulated as far as privacy and data regulation is concerned.

Thus, the humbleness of the purpose limitation provision in Master Directions, 2016 and non-availability of a robust Personal Data Protection Act or other purpose limitation or collection limitation directions prevent desired checks on the FIUs. As a result, in practice, FIUs can access, process and share unlimited personal and financial data of consumers, to profile individuals, target advertisements and sell individuals’ data, among other things. Moreover, the individuals concerned would not know whom to hold accountable, as once consent has been obtained by the FIU, there is no means to find out what data profiling techniques are being used by this FIU and what they are being used for.

In summary, at present, there is no technology layer and the available regulatory layer is insufficient to prevent individuals from being profiled, targeted or surveilled by FIUs or FIPs on the basis of data shared through AAs. Having robust AAs alone, while a step forward, is not sufficient to enable users’ autonomy. Autonomy is relational and therefore, policymakers will need to go a notch further and build tools and/or regulations which protect users from the actions of FIUs may take with user data.

The ecosystem should enable users to choose and switch AA at any time, without being bound by a penalty or lock-in periods. This implies that there should be a sufficient number of AAs competing with each other in the market. In addition, there should be many FIUs, so that users have the ability to choose from a variety

In my interviews with Saurabh Punjwani, Rahul Mathhan and Kamya Chandra, among others, they indicated that the framework aims to equip users with the ability to choose and switch AAs so that there is no oligarchy.

In the actual market, there are four AAs, at the moment: although six account aggregators have received a license of approval from the RBIa, only four have received an operating license so far (Sahamati, 2020a). Because the FIPs and FIUs are common across the entire ecosystem, these first few operational AAs may have first movers’ advantage.

The developers of the ecosystem are optimistic. Vinay (Chief Technologist at Perfios) stated that the first mover may have an advantage, but user experience, transparency, lower failure rates and customer support are differentiating factors between competing AAs, which should enable competition. Vinay drew parallels between the AA ecosystem and the unified payments interface (UPI) ecosystem and was of the view that, just like the UPI ecosystem enables a future of multiple specialised payments apps (for women-first payments, children-first payments, a hyper-secure variant for the armed forces, etc.), so does the AA ecosystem. However, I see a different trend. Despite raising millions, most small wallets and companies were squeezed out by big tech companies due to a range of reasons, including that big companies have an existing user base, large amounts of funds available, etc. (Christopher, 2020). Today, 45 and 34.3 percent of the market are held by Google Pay and Phone Pe respectively (Upadhyay, 2021).13

This illustrates that the developers of the AA ecosystem should be very cautious so as to prevent it meeting the same fate as the UPI ecosystem. If the AA ecosystem fails to enable competition, there would only be one or two dominant players, which means no real choice for the customers, leading to a power imbalance.

Thus, having an ecosystem that enables competition is not sufficient, enforcing competitive practices is equally important. Therefore, the regulators – both the RBI and the Competition Commission of India (CCI) – have an important responsibility. They must identify and eliminate anti-competitive behaviour, such as monopoly pricing, cartelisation by players, customer-locking, and any other market abuse (Uppal, 2020).

Another challenge that will need to be addressed is that many entrepreneurs and institutions are skeptical towards the AA ecosystem and so far hesitate to participate. This is for two main reasons in particular.

1. Lack of clarity with respect to the revenue models of the AAs

Neither the Master Directions, 2016, nor the AA’s self regulatory organisation, Sahamati Foundation, have delineated any clear revenue scheme for account aggregators. In the definition clause of the Master Directions, it is briefly mentioned that account aggregators undertake the business of AA for a fee or otherwise. The fee will be decided by an Account Aggregators’ Board approved policy. Pricing of services will be in strict conformity with the internal guidelines adopted by the Account Aggregator which need to be transparent and available in public domain. However, the Directions do not provide any clarity regarding the assessment and calculation of this fee. This is worrisome, particularly from the consent perspective, because a clear revenue model is necessary to attract new investors in this ecosystem . Malavika Raghavan, researcher and a keen observer of the sector, highlighted:

There exist fundamental economic and operational problems in this ecosystem. The RBI Master Directions clearly state that AAs cannot use data flowing through their systems, but they fail to clarify how an AA can make customer propositions. Policymakers have left a lot of basic questions unanswered.

Until these ambiguities are addressed, the proposed framework, allowing for participation of many AAs, might not become operational in practice. As a result, users’ choices regarding AAs would also be limited.

2. Low level of participation of FIPs and FIUs

Without a sufficient number of FIPs and FIUs in the ecosystem, it will not be possible for AAs to acquire customers. Therefore, it has been a constant endeavour of the developers of the ecosystem to get as many financial service providers as possible onboarded in the ecosystem.14 After two years, eight banks have been onboarded both as FIPs and FIUs (Sahamati, 2020b).

Along with the developers, Sahamati has been at the forefront of these efforts. In an interview, Kamya Chandra pointed out that the RBI is mostly concerned with preventing and addressing financial crises; their focus is not on financial inclusion. Therefore, there is a need for someone else to take up the responsibility of implementing the AA framework, and according to Chandra, “Sahamati’s focus for the last six months, and for the next six months, will just be to make sure that the FIP and FIU modules are live across major banks, allowing for the sharing of a core set of data that’s required for cash flow lending.”

Directions 3(1)(xi) and 3(1)(xiii) from the Master Directions, 2016, seem to further support this quest, as they allow for a wide range of institutions to be FIPs and FIUs. But despite these favourable regulatory conditions, banks have not been very enthusiastic.15 Munish, Co-Founder of Finvu, stated that “to have institutions onboard has been a slow process and has not been the easiest thing. It required a lot of convincing; institutions have been hesitant”.

Vinay, at Perfios, specified three reasons in particular why banks have been slow in adopting the AA framework. First, the impact of Covid-19 prevented the banking industry from being enthused about lending until August/September 2020. In addition, setting up their IT systems in a state of lockdown was not feasible. Second, banks are strictly regulated by the RBI, so in case of any change, they need to notify the RBI and seek permissions. Considering that this ecosystem has the RBI’s blessing, doing so has been easier, but the process still remains slow and time-consuming. And third, it takes a lot of time for a traditional bank to finetune their IT ecosystems to participate in the AA framework, as the current IT systems would require a complete overhaul.

Apart from banks, there are other FIPs and FIUs, such as the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT), under the Ministry of Finance, and telecom companies. It will be an even more complex task to integrate these into the ecosystem, as each of these information providers have unique data structures and the regulations that govern these entities are also varied. For example, the CBDT can share information about individual assessees with Scheduled Banks (Income tax Department, 2020). However, other FIPs and FIUs, such as telecom companies and the Department of Revenue, are not allowed to do so. In addition, rules and notifications under the Income Tax Act, 1961 are at odds with the expansive range of information made available to FIPs and FIUs by the RBI. Similarly, the law does not allow for the sharing of telecom data yet (TRAI, 2017). Thus, due to the legal vacuum with respect to data sharing policies, it will be a long term process to onboard all FIPs and FIUs to fulfil all desired use-cases. This will have a direct impact on entities that wish to seek an AA license: seeing the circumstances, a potential new entrant might be rather hesitant to enter the space.

The ecosystem may have been envisioned with the intention that there would be multiple service providers, i.e. AAs, and that users would have the ability to choose and switch their accounts. But if choice does not exist in practice, users’ bargaining power could be diminished. To encourage more participation there is a need for a strong business model for the AAs and a regulatory policy that would enable competition as well as incentives for FIUs and FIPs to integrate themselves in the ecosystem. Otherwise, the vision of enabling users with ample choice might not come true.

Privacy respecting ecosystems are easier to promote and operationalise as users are less hesitant to give consent when they believe their data will be kept private. Thus, the ecosystem should provide regulatory and technical tools or frameworks to ensure privacy

Let us first examine whether the AA framework’s technical specifications are resilient.

While the RBI’s Master Directions, 2016 provide a framework for the registration and operation of account aggregators in India, its Technical Specifications for Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) provide technical guidance for the development of the AA ecosystem. The Directions and Specifications both require AAs to be data blind. This implies that AAs do not have access to the information that is being transmitted through them. In addition, AAs cannot perform any other business apart from serving as data intermediaries.

AAs being data blind is a positive element. However, this requirement alone is not sufficient to address all privacy concerns arising within the ecosystem. In particular, the current system provides no technology tools or framework for four key privacy issues.

First, while facilitating data transfer by users and FIUs and FIPs, AAs will be collecting metadata such as users’ basic profile information, including name and registered mobile number; which FIPs they are interacting with; and how often they interact with them. There is no technical or regulatory specification to regulate storage or use of this data as per the current Master Directions. This is problematic for two reasons: Firstly, this data would enable AAs to learn which user interacts with which FIUs and FIPs and which FIUs have higher traffic. As the business model of AAs is to charge consumers and FIUs for the exchange of data, they can potentially identify the nature of transactions done by users and FIUs and on the basis of this accumulated metadata, increase the cost for certain transactions for certain users or for FIUs. Secondly, since there is no mandate to encrypt or delete the metadata, the metadata continues to be vulnerable from the moment it is recorded, and if leaked, FIUs can take unfair advantage of this data to manipulate users by increasing costs, targeting ads, etc.

Second, as per the RBI’s Master Directions, 2016, AAs are required to store data for a maximum of 72 hours. However, there is no technological means to enforce the transience of the storage. If stored for longer, the risk of leakage increases (NeSL, 2018; Jagirdar & Bodduluri, 2020).

Third, there are no technological means to assess whether purpose limitation and collection limitation are being observed by FIPs and FIUs, or to enforce these limitations. In the absence of a Personal Data Protection Act and a technology layer that enforces collection and purpose limitation, despite Direction 7.6.2, FIUs could request for unnecessary information and could use this data for purposes for which consent was not obtained, rendering the consent mechanism meaningless.

Fourth, there is no specification that allows for the identification of frauds in this ecosystem. A motivated user can easily create a trail of data to prove the existence of fifty transactions to different accounts in order to get a loan, while in reality, all those fifty transactions would have been made to fifty different UPI IDs created by the user herself. Considering the entire ecosystem has minimal human involvement, it would be very difficult to identify the frauds.

The current technology specifications are, thus, not sufficient to address various existing privacy concerns. However, sometimes what the technology layer fails to address can be resolved by the regulatory layer. For example, GDPR provides for a Data Protection Officer to ensure that privacy by design is being observed by data controllers while creating technologies to collect and process data. Thus, it is also imperative to assess whether the AA ecosystem is governed by a robust regulatory framework.

Currently, there is ambiguity regarding the recognition of AAs as NBFCs. Thus, the RBI’s claim to regulate AAs is also questionable. As per section 45 IA of the RBI Act, the RBI is empowered to register, lay down policy, issue directions, inspect, regulate, supervise and exercise surveillance over NBFCs that meet the 50 – 50 criteria of principal business.16 However, since more than fifty percent of the income of the AAs does not come from financial assets, because they do not technically provide financial activities (Raghavan & Singh, 2020), it has been argued that AAs cannot be termed NBFCs. Moreover, the RBI has failed to clarify the motive and the reasoning behind the categorisation of AAs as NBFCs in formal public documentation (Raghavan & Singh, 2020).

Even if we were to consider AAs as NBFCs, the question of whether the RBI is empowered and has the technical capability to regulate the information flows that are going through the data pipes of the AAs’ networks remains. Raghavan and Singh (2020) highlight that the RBI’s assertion of its intention to regulate all information flows in the financial sector, irrespective of their connection to financial activity, is complex and problematic, as it is beyond the competence and mandate of the RBI to regulate an activity which may not be purely financial, such as the consolidated viewing of data and consents.

However, neither regulators nor individuals have challenged the RBI’s ability to regulate AAs. As a result, the account aggregators are subject to the RBI’s Master Directions and the RBI’s Technical Specifications for API’s, in addition to the Information Technology Act, 2000. However, the Master Directions are not comprehensive and fail to rectify the privacy concerns that have been left unaddressed by the technical infrastructure of the AA ecosystem that I outlined above. The Master Directions do not apprehend apparent privacy risks, such as profiling and surveillance, within the AA ecosystem. The Directions only provide that AAs should be data blind; data collection by FIUs and usage and misuse of data by both FIPs and FIUs are not addressed. Moreover, the Master Directions are silent on excessive data collection through a consent artefact.

As the Master Directions, 2016, are insufficient to regulate data flows, there is a need for a robust and omnibus Personal Data Protection Act that delineates the overarching rights of users and obligations of data fiduciaries and contains provisions for transparency and accountability. However, the AA ecosystem has gone live prior to the promulgation of such a comprehensive data protection régime, which is worrisome. In the absence of a strong data protection law, there is no regulatory framework for the data collection and processing carried out by FIPs and FIUs; there are no means to assess the implementation of the rights and obligations of data subjects and data fiduciaries respectively; and in case of a breach, there is no recourse available for the customers of AA services, among other issues.

Even if the Personal Data Protection Bill had already been promulgated and notified in the Gazette of India, in its current form it would not have been effective, however, in addressing the privacy and consent concerns raised above. The current Bill fails to provide sufficient recourse to the data subject from misuse of data by data fiduciaries. Except when processing personal and sensitive data of children, the Bill does not obligate data fiduciaries to always act in the best interest of data principals.17 Instead, the Bill places high expectations upon data principals by requiring them to look out for their own interests. At the same time, some provisions enable excessive power concentration in the hands of data fiduciaries. This will benefit AAs, FIPs and FIUs, and not the users whose autonomy the Bill and this ecosystem supposedly aim to enable.

Praneeth, a technologist and fintech enthusiast, when discussing the regulatory framework governing the AA ecosystem, highlighted section 14 of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 as one such example that furthers the concentration of power of data fiduciaries and prevents users from exercising autonomy. Section 14 lays down that certain additional grounds can be specified by regulations for processing of personal data without consent for “other reasonable purposes”.

Section 14(1) empowers the Data Protection Authority to specify such other reasonable purposes after considering factors such as the interest of the data fiduciary, the effect of such processing on the data fiduciary, the public interest, and a reasonable expectation of consent. It is disconcerting that the interests of the data fiduciary are emphasised in this section.

In addition, section 14 grants the Authority the power to determine whether the provision of notice under section 7 will be applicable or not, depending on the nature of the reasonable purpose. Given that the grounds for defining reasonable purposes prioritise the interests of the data fiduciary, and not the interests of the data principal, it is particularly problematic to further redact the obligations under section 7.

Section 14(2) of the draft Bill provides a list of exemptions or instances in which personal data can be processed without seeking consent for reasonable purposes, which may include mergers and acquisitions, credit rating, recovery of loans and the detection of fraud. Praneeth considered many of these exemptions problematic because they empower data fiduciaries excessively. For example, if “credit scoring” is accepted as a reasonable purpose, this activity will be plagued by opacity. While traditional credit scoring comes with its own biases, the age of datafication, big data analytics and AI tends to magnify these biases, further impacting the communities concerned (Waddle, 2016; Eveleth, 2019). Moreover, it must be noted that companies have started to garner data across platforms, including from social media, to decide an individual’s credit worthiness, going far beyond traditional metrics (Yanhao et al., 2015). While credit scoring may help to ensure access to credit for some, seeing the intrusive data gathering it often entails, such scoring should at a minimum be done with the consent of the individual concerned. However, the Bill would allow FIUs to ask for any kind of data under the garb of assessing creditworthiness, and users would not even have an option to deny consent because consent is not a pre-condition as per this section.

Thus, if the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 version is promulgated and would be applied to the AA ecosystem, it would not prove to be an effective regulatory framework for the users of AA services to exercise their autonomy and consent. This implies that to make the AA ecosystem resilient with respect to the privacy of its users’ data, the ecosystem should be strengthened with tools and regulations that are robust enough to protect users’ data and choice. Instead of instilling trust and confidence in the users, the current state of regulations overseeing the framework are worrisome and thus, should be reconsidered to enable the intent of the AA framework, i.e. autonomy of the users, while ensuring privacy.

Transparency measures need to be proposed by the regulators, so that users can become aware of the conditions and mechanisms deployed by data fiduciaries and thus, express their consent freely

The RBI’s Master Directions, 2016, do prescribe some transparency measures that will allow users to trust the tools and express their consent more freely. In particular, they mandate that the names of the agencies that have been given licenses to be AAs, FIPs, and FIUs be made public and that, incase of revocation of the license of any agency, the announcement, too, will be made public.

However, these measures address only a very limited set of concerns. For example, they do not obligate data fiduciaries to inform users about data breaches or leaks. In contrast, the EU GDPR and even the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, provide for a number of transparency measures. For example, sections 23, 25, 26, and 28 of the Personal Data Protection Bill provide for transparency measures which include transparency in the processing of personal data; reporting of personal data breaches; classification of data fiduciaries as significant data fiduciaries, obligated to provide a higher level of care; data protection impact assessments; and maintenance of records by data fiduciaries. Unless all these measures are rolled out and the regulators are enforcing these mechanisms, it will be difficult for users to consent meaningfully because they will continue to be unaware of breaches, of the impact of technology used to process their data, etc. Thus, to enable autonomy, it is imperative to ensure all the conditions including transparency should be met.

Consent should be sought proactively #

THE PRINCIPLE: The communicative approach to consent was developed in the early 90s by scholars like Pineau (1989), who argued that the person who is seeking consent for a sexual act, whatever their gender may be, must obtain consent in the affirmative from their sexual partner. Thus, this approach seeks to shift the burden of proving assent upon the person who is initiating the act. It simultaneously ensures that the partner — often a vulnerable person, such as a woman, trans person, or queer person — will no longer be required to prove that they expressed dissent.

This approach came into existence because earlier, the law generally required women to prove non-consent beyond a doubt. As this often is challenging, it was therefore presumed that the majority of sexual interactions are consensual. The communicative approach to consent was an attempt to address this shortcoming.

RELEVANCE: In the current data governance régime, consent is considered a means to enable privacy self-management. Thus, the burden to assess notices and express consent lies upon users or data subjects. However, once consent is obtained by the data fiduciaries, there is no means to audit that consent or find out how meaningfully it was obtained (Solove, 2013). In other words, in the current data protection régime, data fiduciaries seek consent at the very initial stage for all future acts through vague and ambiguous policies (Strahilevitz, 2013), and through opt-out methods (wherein parameters of consent are pre-chosen) that prevent individuals from expressing meaningful choice. Thus, consent obtained as per the current régime cannot be considered proactive, as the burden to prove dissent continues to lie on users.

If the AA ecosystem is to address these deficiencies of current consent regimes, AAs, FIUs and FIPs should bear the burden of proving beyond a doubt that they have pro-actively sought explicit consent for a specific purpose at every instance. In no circumstance should consent be presumed or assumed.

ASSESSMENT: In what follows, we will explore three conditions that need to be fulfilled by the data fiduciaries in the AA ecosystem if consent is to be obtained proactively and will investigate whether the data fiduciaries have already complied with these practices.

Consent mechanisms should be opt-in instead of opt-out

In interviews with Munish (Co-founder of Finvu) and Vinay (Chief Technologist at Perfios), it became evident that different types of consent artefacts will be used for different use cases within the ecosystem. For example, if consent is being sought for a lending use-case, the parameters of consent will probably be predefined and sometimes pre-chosen as well (meaning that will not be possible not to agree to providing the data), because in such a use-case, the FIUs bear a high risk; by seeking a certain amount of data, they hope to be able to assess their risk properly and thus mitigate it. However, in use-cases such as asset management, where the user is at higher risk, the user will have the ability to opt-in and customise the consent artefact. In other words, the system does not consistently follow an either-or approach. Instead, the mechanism on the basis of which consent will be sought, i.e. opt-in or opt-out, depends on the service that a consumer or user aims to seek.

While the flexibility of the AA ecosystem is acknowledged, research on status quo bias (Kahneman, Knetsch & Thaler, 1991) has highlighted that opt-out mechanisms do not allow users to express consent meaningfully, as users tend to choose the option that is presented as a default, despite having an alternative option. Moreover, Jolls and Sunstein (2005) have noted that people suffer from consent fatigue online and frequently do not wish to engage with privacy notices. In fact, people develop badger blindness: they get so accustomed to certain notifications that they do not opt-out or customise consent and just accept whatever option has been set as the default for them.

In order to prevent badger blindness and to obtain consent from people proactively, opt-in mechanisms have proven to be great nudges. Unlike a default opt-out option which automatically assumes consent, an opt-in mechanism creates an opportunity for a user to realise that they will be parting with their data and to assess and express, or deny, consent in a proactive manner.

Since AAs aim to seek meaningful consent, it is imperative they adopt opt-in mechanisms for all use-cases. It may be true that for certain use-cases, such as lending, wherein FIUs bear high risk and the financial instrument is strictly regulated, a certain amount of data is necessary. However, even in such cases the user should be able to effectively exercise their autonomy; pre-chosen or already opted-in options will affect the effectiveness of the system to seek meaningful consent.

Wherever consent is obtained, it should be clear that the response is “yes/affirmative”

The RBI’s Master Directions provide that consent artefacts should be auditable and verifiable. However, the Directions, or any other document, do not delineate the definition of audit; thus it cannot be stated concretely what auditable exactly means according to the existing regulatory framework.

In conversations, early adopters and advocates of the AA ecosystem such as Rahul Matthan (Partner at Trilegal), Vinay (Chief Technologist at Perfios) and Munish (Co-founder of Finvu), explained that at the technical level, an auditable consent artefact in the AA ecosystem has been interpreted to mean that all consents that are created and revoked are logged and stored in a server maintained by the AA. This enables all users, AAs, FIUs and FIPs to be informed about whether consent was obtained, when it was obtained, for what purpose, and if it has been revoked. Thus, if this feature is deployed as envisaged, it will enable all stakeholders in the ecosystem to learn about the response of the user when consent is requested, creating a means to ascertain whether the user has expressed their consent in the affirmative.

As the tools mentioned in this discussion are still being developed and introduced, I could not independently assess this functionality, using the application.

No convoluted terms or phrases, which may make it difficult for a person to understand what the exact purpose of data collection is, should be used while seeking consent

In conversations, the developers and promoters of the AA apps highlighted that the AA ecosystem will seek consent granularly, i.e. step by step, from users, so as to enable users to transfer and manage their financial data. They also noted that the privacy policies will be easy to read and comprehend. And, on the basis of information available on Sahamati’s website (Mahesh, 2020) and in the video about the application prototype available on Finvu’s website (Finvu, n.d.), it does seem that the consent artefacts generated to seek information on behalf of FIUs are simple, and are being further simplified (Mahesh, 2020).

However, AAs as service providers use old mechanisms to seek consent from users. They have bundled up and hyperlinked the terms of service and privacy policies, which are lengthy, full of legalese, and not very easy to understand. For example, in the terms of use of the OneMoney app,18 under the clause titled “Third Party Accounts”, it is stated that “you hereby appoint Company as your agent”. One cannot expect every individual wishing to use AA services to be aware of the meanings and implications of terms such as “agent” and “lawful attorneys”, which is used elsewhere in the terms of use, among others. Thus, for many readers it may simply not be possible to understand the entire policy. And unless a user expresses their consent after reading and understanding the policy, the consent obtained cannot be termed meaningful (Solove, 2013 ; Cohen, 2017). Such an approach is, therefore, counterproductive to enabling user autonomy and seeking informed and granular consent, as this ecosystem aims to do. Moreover, this approach is not limited to OneMoney: the same mechanism has been adopted by Finvu (Finvu, n.d.) in its prototype as well.

Even though the FIUs in the AA ecosystem imbibe the principle of granularity while seeking consent from users, the way AAs seek consent themselves, thus, remains a weakness: the consent artefact remains a bundled-up notice, that is hyperlinked and full of legalese. This weakness can be resolved only if AAs revisit their means of seeking consent.

Consent is specific, continuous and ongoing #

PRINCIPLE: When consent is approached as a contract, it fails to account for the changing conditions and realities of an individual’s life. In a contract-approach to consent, once a person has expressed their consent for a sexual act and a certain level of intimacy is established between the two individuals, there is no means to withdraw consent, and consent for one act is often assumed to be consent for the following acts too (Cahill, 2001). This, however, is not necessarily correct: a person may not be interested or keen at a later stage, and may wish to pause or rescind from the act while in it or even before getting into it.

In this way, the contract-approach to consent therefore not only fails to acknowledge the spontaneity of sexual consent, but also enables blaming and shaming. People who wish to or actually withdraw consent during an act may start to doubt themselves, often resulting in incomplete and coerced consent forming the basis of the sexual act. Moreover, as the presumption is that consent once given cannot be altered later, the contract approach frequently results in people being blamed for exercising their autonomy (Alcoff, 2009). In contrast, to ensure that individuals can seek pleasure on their own terms, consent must be specific, continuous and ongoing Gruber (2016).

RELEVANCE: In earlier research, Kovacs and I (2020) noted that in the data protection régime, consent, once obtained by data fiduciaries, is often taken for granted (GPEN, 2017).

Thus, to prevent users from being trapped in a data ecosystem, the AAs, along with other technology frameworks, should ensure that consent is obtained for a specific purpose, and is continuous and ongoing, for a number of reasons. First, the ecosystem is being built to offer various products and services within a sector. For example, AAs in the finance sector aim to enable customers to seek loans, wealth management advice and insurance, among other services. But consent obtained for one particular purpose cannot be blindly assumed for another. Second, the time period for which an individual may invest in such an ecosystem could be very lengthy and their decisions with respect to consent might change during that time. And, third, the risk and the stakes with respect to financial and health decisions in particular are very high and subject to change over the course of the lifetime of a person. Thus, consent should not be taken for granted, to ensure control and autonomy to an individual over the long term.

ASSESSMENT: Thus, we look at four conditions that can help us evaluate to what extent the above mentioned principle has been adopted by the current AA framework.

Consent should be sought every time the purpose of usage of the data changes or when the user of the data changes

In the current consent régime, whether in the existing online banking system or on various social media websites, the norm is to seek consent at one place, in a single instance, and through a single form. This mechanism of seeking consent upfront for all subsequent transactions has proven to be ineffective in seeking informed consent. When data is collected to provide a particular service or a product, that data is often kept for a long time and reused for multiple purposes in the age of data aggregation and networked environments. Moreover, when the data is processed over and again, this is often for purposes which were not thought of or explicitly mentioned at the time of data collection. For consent to be meaningful, it is therefore imperative to seek the consent of a user every time the purpose for which the data is being used or shared is changing or the user of data is changing. For example, in banking, consent for data collection should be sought at the time of opening a bank account, again if later that data is shared with a third party, etc.

The account aggregator ecosystem aims to address the problems that arise from obtaining consent through one form at a single instance by instead seeking granular consent, obtaining separate consent for different purposes and on different occasions. As Rahul Matthan (Partner at Trilegal) noted in our conversation, DEPA and AA are frameworks that enable FIUs to seek consent on different occasions and not upfront, and that is a positive step.

However, one challenge that continues to exist is that this step-by-step approach to consent has not been coded into the regulatory framework for any of the products or services. Moreover, as noted earlier, in the absence of robust data protection régime FIUs can continue to ask for excessive data from individuals, the mere capability of the AA ecosystem to obtain consent continuously will not be sufficient to encourage FIUs to imbibe this principle. The latter in particular remains an important limitation.

Even after users express consent, they should be empowered with the ability to view, edit and delete their data

From the very inception of the AA ecosystem, we saw that this technology was conceptualised to empower individuals to view their accounts and data across financial institutions in a common format. It was only later, in 2016, that the RBI modified the functionality of the AAs from being mere consent viewing dashboards to data intermediaries and consent managers (Raghavan & Singh, 2020). Thus, one of the primary functions of the AAs continues to be the ability of a user to view their financial data, normally resting in silos, consolidated and in a common format.

The RBI’s Master Directions, 2016 provide that an individual can access a record of the consents provided by them, along with the FIUs with whom the information has been shared. Moreover, while discussing the privacy of the records that are to be maintained by AAs to enable users to view these consents, Vinay (Chief Technologist at Perfios) highlighted that the AA client would store these consent logs in an encrypted format, which can only be decrypted on the customer’s handheld device or computer. This means that individuals will have complete control over their consent data as the key to encryption will be generated by the user within their handheld device only. If any entity wishes to access this data they will have to seek an individual’s permission and key to decrypt the data.

Along with the consolidated view of data, the RBI’s Master Directions also equip the users to pause (temporarily) or revoke (permanently) consent. However, as of now, no regulatory direction or technology tool enables individuals to edit the data, once fed into the AA ecosystem, at any stage. This is problematic because there may be mistakes in an individual’s data, or the data may undergo a change. In such cases, even if an individual wishes to correct their data so as to express their consent meaningfully, the ecosystem as it is does not allow them to do so. For consent to be meaningful, an individual should be able to at least raise a request to edit the incorrect or changed data.

Moreover, when an FIU raises a request to seek data, it is called a consent artefact. This consent artefact has information about the type of data that is being requested, the time period for which it is sought, the type of fetch it is, etc. But there is no provision for the user to view the actual data that an FIP transfers to an FIU before the transfer. Thus, the system expects an individual to remember what data resides with each FIP. It only allows an individual to view the consent requests and the data that is transferred after it is shared through the AA ecosystem. However, because many users will have set up their financial accounts a long time ago, they may not be aware what information of theirs is residing with FIPs. In addition, most banks that are FIPs in this ecosystem have such lengthy terms of conditions and data policies that users are not even fully aware of the data that resides with them. Thus, when an unaware user gives consent, their decision might have serious consequences, including unnecessary delays that may affect their livelihood.

To seek meaningful consent, users should be allowed to view the data that is being transferred to the FIU prior to the transfer, and in case the user is of the view that the data provided is incorrect, users should be allowed to raise a request to address and edit the discrepancies prior to transfer, to enable autonomy and prevent adverse consequences.

Users should be allowed to revoke consent at any time, and the mechanism to exercise that right should be seamless