Criminalising dissent? An analysis of the application of criminal law to speech on the Internet through case studies

A report by

Shehla Shora & Anja Kovacs

Abstract

Over the past two years or so, news reports of people getting arrested for Facebook posts or tweets have managed to stir a public debate about laws governing the Internet in India. With the arrests of Ambikesh Mahapatra, Aseem Trivedi and Shaheen Dhada, the issue of criminalisation of online speech and expression has caught mainstream attention. But the shape and details of this phenomenon remain surprisingly underexamined. On which occasions does the application of criminal law stir controversies? Who are the actors involved in such cases? This study seeks to make a beginning to expanding our understanding of these under-researched issues in the Indian context, by examining in depth seven famous Indian cases in which criminal law has controversially been drawn on in an attempt to stifle free speech on the Internet.

Introduction #

Over the past two years or so, news reports of people getting arrested for Facebook posts or tweets have managed to stir a public debate about laws governing the Internet in India. With the arrests of Ambikesh Mahapatra, Aseem Trivedi and Shaheen Dhada, the issue of criminalisation of online speech and expression has caught mainstream attention. But the shape and details of this phenomenon remain surprisingly underexamined. On which occasions does the application of criminal law stir controversies? Who are the actors involved in such cases? Despite growing concern, and with the exception of section 66A of the Information Technology (Amendment) Act, 2008 (henceforth the IT Act), remarkably little detailed information is available till date about the ways in which criminal law impacts free speech on the Internet in India.

There is reason for worry. In his report on the Internet and freedom of expression of June 2011, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, Mr. Frank La Rue, expressed his concern that ‘legitimate online expression is being criminalised in contravention of States’ international human rights obligations, whether it is through the application of existing criminal laws to online expression, or through the creation of new laws specifically designed to criminalise expression on the Internet’.1 As governments across the political spectrum are increasingly seeking to assert control over the Internet, reports have seeped in from Thailand, over the UK, to Egypt, of bloggers, tweeters and other Internet users being charged, and sentenced, under criminal law.

While in certain exceptional cases criminal action may indeed be justified, there is, thus, a growing concern that with the new possibilities for free expression that the Internet allows, criminal law is increasingly being used to stifle legitimate expression, either because it offends, shocks or disturbs, or because it is disagreeable to governments or other powerful entities in society, or both. Seeing that criminal laws aim to function as severe deterrents – not only in their application but also through their mere existence – their increasing use, La Rue argues, can not only lead to a growing number of criminal sentences to penalise speech, but also to greater, and troubling, levels of self-censorship as Internet users fear coming into conflict with the law.

This study seeks to make a beginning to expanding our understanding of these issues in the Indian context. It examines in depth seven famous cases in which criminal law has controversially been drawn on in an attempt to stifle free speech on the Internet in the country.2 In each case, victims faced threats of prosecution, actual arrests or lawsuits, under either the IT Act or various sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), for content that they had posted online.

By focusing on these high-profile cases, we hope to unearth more information about:

• which are the most controversial grounds for criminalisation

• in what circumstances are these laws mobilised

• who are the political and/or social forces who drive their contentious use.

The focus on contentious cases is, of course, not to say that the use of criminal law in other instances is necessarily unproblematic. As UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, Frank La Rue, has pointed out, ‘imprisoning individuals for seeking, receiving and imparting information and ideas can rarely be justified as a proportionate measure to achieve one of the legitimate aims under article 19, paragraph 3 of the ICCPR’.3 But by starting to unearth some of the central points of conflict in this regard where the Internet is concerned, this study hopes to contribute to more effective future advocacy and action in this field as a whole.

This research – including the selection of the cases to be discussed in depth – was conducted in a two-step process. In the first instance, as our assumption was that contentious cases would be reported in the media, any mention of a relevant case that we came across in a media report was added to a table that became an Index of Cases. Where possible, descriptions of cases as gleaned from media reports were supplemented with information available in online legal archives. The complete Index of Cases can be found in Appendix A.

The focus of the Index is on cases from the past five years. However, as it soon became clear that the Index could be a useful resource for others to draw on as well, we decided to also include several landmark cases that are considerably older. For example, the Delhi Public School case, which resulted in the Chief Executive of baazee.com getting jailed, was extremely important in shaping the debate on intermediary liability. This case dates back to the year 2004. Also, not all cases included resulted in prosecution. For example, veteran journalist Barkha Dutt’s legal notice to blogger Chaitanya Kunte did not result in an actual complaint or lawsuit; we decided to include this case anyway because this development sparked a fierce debate on free speech in online circles.

Even though the list is not exhaustive, to our knowledge it is the only attempt to collate such a large number of cases as discussed or reported in the media so far. All cases included are from India, although parties involved in some cases are based abroad.

The exercise of building the Index in itself provided some interesting insights. We had identified beforehand five probable grounds on which speech would be contentiously criminalised, and had aimed to attribute to each case one main ground. These grounds were hate speech, security (be it cyber security or national security), defamation, obscenity, and hurting religious feelings. However, interestingly, there were very few cases in which security reasons emerged as a stated ground for the invocation of criminal law. At the same time, the number of defamation cases was very high. Many cases could fit into more than one category.

One should, however, be careful to draw any conclusions regarding the pervasiveness of the problems indicated from the Index. For example, a possible explanation for the large number of defamation cases could simply be that these often involve powerful entities and that it is for this reason that such cases easily become the subject of news. Thus, while the Index of Cases provides a sense of the range of issues that the application of criminal law to online expression raises, it does not allow drawing any conclusions regarding their individual prevalence.

In the second stage of the research, a limited number of cases listed in the Index were then studied in greater depth. The main driver for the selection of these particular cases was the diversity and importance of the issues or questions raised by each of them. What was the particular contribution that this case had made to the debate? In line with our aim of mapping the most contentious aspects of criminal law in India as it relates to online speech, it was this question that primarily guided our choices.

News sources were used as preliminary sources of information for the analysis of the cases. Legal documents were accessed wherever available. An attempt was made to reach all parties involved in each case but this was not always possible. Where telephonic or email conversations with the parties involved are reproduced in part or in full, this is with their knowledge and permission.

We then used the in-depth description of each case as an opportunity to examine the various laws that each case draws on and to investigate whether the wording of some of the clauses is problematic.

Seven cases were selected in this manner, and the bulk of the remainder of this report is devoted to their analysis. The IIPM case is an example of how defamation law can be used to create a chilling effect on critics to prevent dissemination of truth that is in the public interest and how it can also be harmful for investigative journalism. The Aseem Trivedi case illustrates how artistic freedom and political criticism can be curbed in the name of the national interest, respect for national symbols and so on. The case involving Vinay Rai shows how anyone can set the law into motion without going through due process. It raises important questions regarding the legal framework for intermediaries in India, as well regarding some of the challenges that laws intended to ensure the peaceful coexistence of India’s many communities pose in the Internet era. These challenges are further expanded on when discussing the Shaheen Dhada case, which also raises important questions regarding what is private and what is public on the Internet. Finally, the cases of Ambikesh Mahapatra, KV Rao and colleague and of Henna Bakshi are used to highlight the perverted use to which obscenity provisions are sometimes put in the context of complaints that seem aimed at settling scores or ‘teaching someone a lesson.’

Two further points on inclusions and exclusions from the study deserve to be made here. First, defamation suits can be either criminal or civil in nature: where there is a civil suit, there is usually a claim for damages; a criminal complaint for defamation can result in both jail and in fine. IIPM has used both as a strategy, and although this paper strictly speaking deals with the criminalisation of speech, both will be discussed here. This is because to illustrate the full impact of these sections on freedom of expression, it is essential to provide the context in which the criminal complaint needs to be seen: a series of civil defamation suits for extremely high amounts, often filed in remote parts of the country against critics of the institution. Such practices amount to what is known as SLAPP suits (strategic lawsuits against public participation) and are a common and, unfortunately, fairly effective method to stifle criticism, to which criminal defamation complaints add further force.

Second, it deserves to be noted here that it is also increasingly common to use a combination of intellectual property rights (IPR) legislation and IPC provisions, especially defamation law, to claim disproportionate amounts as damages and also to block and censor content. This combination of IPR legislation and IPC provisions to obtain private injunctions and to claim damages is emerging as a new form of censorship. In the Tata vs Turtle case, for example, business group Tata sued Greenpeace for an amount of Rs. 100 million, on grounds of defamation and copyright infringement. Greenpeace, as part of a campaign targeted at Tata, had used Tata’s logo in an online spoof game criticising its practices that, Greenpeace argued, were harmful to sea life.4 However, because of the relatively recent emergence of this strategy and because of the fact that it has received relatively little media attention so far, IPR is not discussed in this study. We recommend separate research on this issue.

Throughout the analysis of the seven cases that we will be discussing in this study, weaknesses of legal provisions, including the now infamous section 66A of the IT Act will be highlighted. Broader procedural challenges will receive ample attention as well. However, before we start this detailed examination, it is important to provide an overview of the background against which our analysis has to be understood. When and how did online free speech in India become such a contested topic?

Contestations around Free Speech on the Internet in India #

Internet use in India is increasing, and so is the number of cases filed, year-on-year, under the laws governing various Internet crimes. What can the figures tell us?

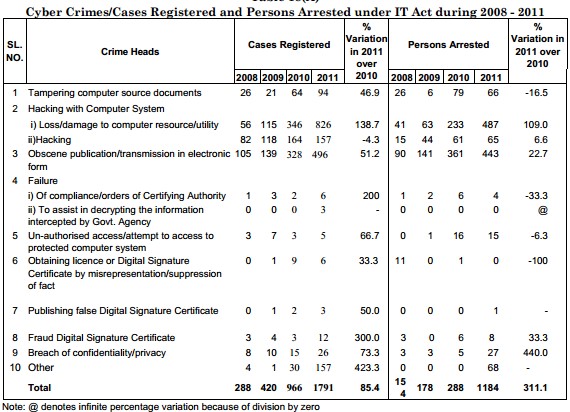

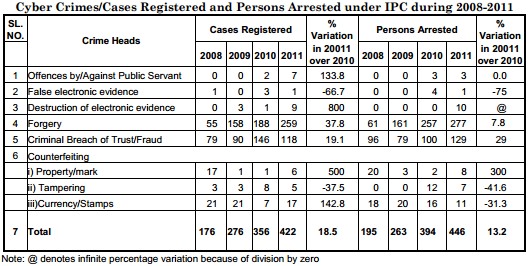

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report, 1791 cases were reported under the IT Act in 2011. This marks an 85.4 percent increase over the previous year. In addition, 422 cases registered under the IPC involved the use of computers and were also treated as cyber crimes.5 But the extent to which these figures refer to cases that could potentially concern freedom of expression, unfortunately, remains unclear.

As Table 1,6 above, illustrates, in 2008 and 2009, cases related to ‘obscene publication/transmission in electronic form’ formed the highest fraction of cases registered under the IT Act (36 percent and 33 percent respectively). These could potentially be free speech cases. While in 2010 and 2011, the importance of this category was surpassed by that of cases related to ‘loss/damage to computer resource/utility’ (35 percent and 46 percent respectively), the number of obscenity cases continued to rise, with 2011 seeing a 51 percent increase over the previous year.

To what extent freedom of expression might also be implicated in other categories listed in this table remains, however, unclear. Moreover, as Table 2,7 below, illustrates, where IPC sections applied to cybercrime are concerned, the NCRB report is even less helpful. Though possibly the most authoritative source on this issue, the NCRB report does not contain enough information on cybercrime related cases to draw any conclusions about the effect of criminal law on free speech.

While numerous arrests have been made in cybercrime related cases, reports indicate that the conviction rate so far under the IT law, which was enacted in 2000 and amended in the year 2008, remains very low.8

This could be explained by several factors. Several cases may be ongoing, given the fact that the law is new and the judicial process slow. Lack of proper evidence and evidence-gathering techniques could be an important factor.9 Besides this, some of the laws themselves may be overly broad or problematic in other ways, allowing arrests where none should be made.10 Overreach by law-enforcement agencies cannot be ruled out either, as they are believed to have acted under pressure in certain cases.11 For example, professor Ambikesh Mahapatra was arrested overnight for criticising the Chief Minister of his state; cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested for publishing cartoons against corruption in India that were highly critical of the government; small-scale industrialist S Ravi was arrested on the basis of a mere email from a senior Minister’s son; two girls in Mumbai were arrested under pressure from Shiv Sena members. In all of these cases, as will be discussed later in this report, some or all of the charges were dropped later, indicating that there was overreach initially.12

While the NCRB data may not shed much further light on the matter, that both the law and law enforcement might affect freedom of expression on the Internet negatively was widely recognised following the arrest of Shaheen Dhada and her friend in Mumbai; the young women were arrested because the former had written a Facebook post questioning a shutdown of Mumbai after a local political leader passed away and the latter had liked, commented on and shared the post (more detail on this later). Following their widely criticised arrest, the Department of Electronics and Information Technology, on the initiative of the IT Minister, issued ‘tougher’ guidelines for arrests to be made under the controversial section 66A of the IT Act;13 India’s Supreme Court admitted a public interest litigation challenging the constitutionality of the particular section;14 Aseem Trivedi, the cartoonist who was booked under section 66A, went on hunger strike for over a week;15 a government-owned telecom provider’s website was hacked by hacktivist collective Anonymous in support of Aseem Trivedi’s fast;16 and the Indian Parliament took up a discussion on section 66A.17

The events surrounding section 66A of the IT Act played a crucial role in drawing mainstream attention toward and galvanising support for the movement against Internet censorship, and section 66A will be a consistent presence throughout this paper. The provision allows for the arrest of any person who ‘sends messages that are grossly offensive or of a menacing character’ and false messages that cause ‘annoyance or inconvenience’, among other things. As we will detail later in this paper, the wording of the provision has come under serious criticism as it is overly broad and gives wide powers of arrest to the police who may not even understand social media and political satire very well.

But section 66A of the IT Act is not the only provision that is used to silence legitimate speech on the Internet in India, and the obvious sense of alarm caused by arrests under section 66A needs to be understood against the backdrop of wider concerns over India’s censorship of the online space.18

Free speech activists across the country were deeply alarmed when the New York Times reported that Kapil Sibal, Minister for Communications and Information Technology, had asked Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Yahoo! and the India Times Group to prescreen user content from India and to remove disparaging, inflammatory or defamatory content before it goes online.19

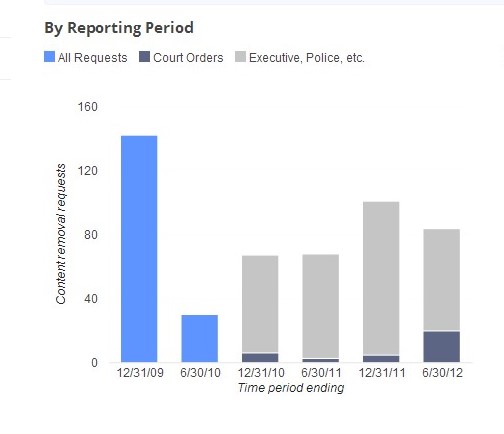

Google’s Transparency Report provides some insight into the number and the nature of takedown requests received from the government or its agencies, police departments, courts, etc. While the number of content removal requests that the Government of India (including courts, police, etc.) made to Google was considerably lower in 2012 than in 2009, and while the fraction of requests that is backed up by a court order seems to be on the increase, the fact remains that the overwhelming majority of these requests continue to be made by the police or government officials without the courts’ backing20 (see Figure 121).

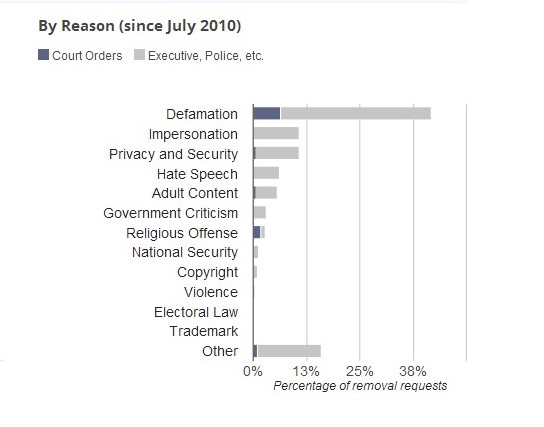

Interestingly, in line with our analysis of the Index of Cases, the top reason cited by the government for content removal requests was not security, not even hate speech, but defamation, with more than 40 % of all requests since July 2010 citing that reason. Court orders could have resulted from private disputes or from disputes involving the government or politicians – the report does not make a distinction or provide any break up (see Figure 222).

Google clearly hasn’t been convinced by the legitimacy of these requests, as its compliance rate has gone down drastically over the years, from 77 percent in December 2009 to around 30 percent more recently.

Figure 1. Summary of All Content Removal Requests Received by Google from the GoI, By Reporting Period

Figure 2. Summary of All Content Removal Requests Received by Google from the GoI since July 2010, By Reason

Other instances of government-ordered blocks have been reported. In 2012, as renewed violence between Muslims and Bodos, an indigenous tribe, in India’s Northeastern state of Assam coincided with an escalation of violence between Rohingya Muslims and Buddhists in Myanmar, this opportunity was used by some to spread rumours among India’s Muslims about massacres that had never happened.23 For example, one Urdu publication passed off an image of a Tibetan monk standing beside piles of corpses after an earthquake in 2010 in eastern Tibet as the picture of a Buddhist monk in Myanmar after what was described as mass murder of Rohingya Muslims. The wrongly-contextualised picture was widely shared on Facebook and is believed to have sparked a fury among Muslims, ultimately leading to threatening text messages and, it is believed, a mass exodus24 of Northeastern Indians from Bangalore and some other cities of India.25 To arrest the further spread of rumors, the government banned mass SMS26 and issued plain paper orders to Internet service providers (ISPs) directing them to block a host of URLs, without citing any sections of the IT Act or of the IPC.27

In doing so, the government was exercising its powers under section 69A of the IT Act, ‘power to issue directions for blocking for public access of any information through any computer resource’: the blocking rules under that section – formally known as the ‘Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Blocking for Access of Information by Public) Rules 2009’ – do not require the government to issue anything more than plain paper orders, nor does the government have to accord a reason for the blocking order or cite any provisions of law. An analysis of the blocked URLs shows, however, that many of these URLs ought not to have been censored: this includes the Twitter handles of several right-leaning journalists and groups, besides a parody account of the Prime Minister.28

Though the above incident was said to have been the first time that the government resorted to using its powers under section 69A, since then it has done so again on several occasions. In November 2012, it blocked access to 240 URLs related to a film that is believed to have hurt the religious sentiments of Muslims.29 In February 2013, the Department of Telecom (DoT), following a court order, issued an order to all ISPs to block 78 URLs, 73 of which were related to a business school called the Indian Institute of Planning and Management (IIPM).30 At about the same time, the DoT also asked ISPs to block 55 URLs, mostly Facebook pages related to Afzal Guru, a Kashmiri hanged in connection with the Parliament attack case.31

Take-down requests received by Google, Facebook, etc. are made under a host of provisions including, but not limited to, the Intermediaries Guidelines under section 79 of the IT Act, also commonly known as the IT Rules of 2011. The IT Rules require Internet intermediaries to ‘act within thirty six hours’ of being notified about content that is ’obscene,’ ’harassing,’ ’libelous,’ ’hateful,’ ’harms minors’ or ’infringes copyright’ – or risk prosecution.32 As will be discussed later in this report, examples of intermediaries being prosecuted for content hosted on their websites do exist. There is therefore a considerable threat that companies might comply with such orders without questioning, in order to avoid prosecution. There is also apprehension that the very existence of such laws may force the public at large into self-censorship. A ‘policy sting operation’ by the Centre for Internet & Society (CIS), Bangalore, showed that six out of seven intermediaries complied with frivolous and fraudulent complaints.33

Industry sources report that procedural provisions like sections 91 and 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) are also often cited in takedown notices, on pretexts such as ‘gathering evidence’ and ‘maintaining public order’ respectively. Section 91 requires any person in possession of a document or thing that is required in an investigation, inquiry, trial or other proceeding to produce such document or thing upon a summons or written order by a Court or police officer in charge of a police station respectively. Section 144 provides District Magistrates, Sub-divisional Magistrates and other Executive Magistrates thus empowered by the State government to ‘issue order in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger’, i.e. where such direction ‘is likely to prevent, or tends to prevent, obstruction, annoyance or injury to any person lawfully employed, or danger to human life, health or safety, or a disturbance of the public tranquility, or a riot, or an affray’. Offline, section 144 is frequently used in situations in which public order is perceived to be under threat.

India was ranked 131st out of 179 countries in the 2011 – 2012 Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Press Freedom Index.34 In the 2013 report, India has slipped nine places further down.35 India was also added to the list of countries ‘under surveillance‘ in the RSF survey of ‘Enemies of the Internet‘ released in March 2012. For purposes of comparison, other countries in the ‘under surveillance’ category include Russia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia and Sri Lanka.

According to a further RSF report, the Indian government publicly denies accusations of heightened censorship post the 26⁄11 attacks on Mumbai.36 However, even as the government denies accusations of Internet censorship, the IT Minister, Mr. Kapil Sibal, has repeatedly said that the online is different from the offline and, hence, needs to be treated differently. The most recent instance of him saying so was on 6 March, 2013,37 when a resolution against section 66A of the IT Act was taken up for discussion in the Parliament. That the government treats the online different from the offline supports accusations that a new censorship régime has been put into place.

As stated at the beginning of this paper, a detailed investigation of this new landscape so far has, however, been missing. Is the government indeed the primary actor in this new landscape, as often seems to be imputed in media reports? Apart from takedowns and blocks, does it resort to arresting people as well? And who pays the price for any changes to the censorship régime that are being made?

This study seeks to make a beginning to answering some of these questions by analysing in greater detail seven cases that received widespread public attention for the misuse of criminal law to the detriment of freedom of expression. It is to these cases that we turn our attention now.

Defamation: IIPM vs. Critics #

The Indian Institute of Planning and Management (IIPM) is a privately run business school with its main campus in Delhi and eighteen branches across India.38 Arindam Chaudhuri, who is the honorary dean of IIPM, has become synonymous with the institution’s name ever since he started projecting IIPM as the premier business school of India, with the well-known tagline ‘Dare to think beyond the IIMs’. The Indian Institutes of Management or IIMs are a group of thirteen, publicly run yet autonomous management schools; they are regarded as the premier management schools of India known to attract talent through a highly competitive examination.39 IIPM, with its relatively easier admission process, managed to tap into the ‘corporate dream’ harboured by thousands of young Indians.40 At the same time, IIPM has its fair share of critics due to some of its allegedly questionable practices.41

In 2009, Maheshwar Peri, editor of Careers360 magazine and publisher of Outlook magazine faced a complaint of criminal defamation by IIPM over a 2008 article in Outlook written by Peri, which was first in a series of articles through which he sought to expose bogus universities that had cropped up in various parts of the country and which were defrauding students.42

A few other articles in the series were in the offing. For example, ‘IIPM — Best Only in Claims?’ was published later in Careers360.43 The latter article reported, among other things, that while IIPM claimed that its students were eligible for MBA degrees from the International Management Institute (IMI), Belgium, the Accreditation Organisation of the Netherlands and Belgium did not recognise IMI. Also it reported that following a local agitation against the opening of a new campus in Dehradun, the state government of Uttarakhand had asked the Uttarakhand Technical University to conduct an enquiry into the activities of IIPM, with which IIPM did not co-operate.44 The investigations revealed that IIPM could not in any circumstances award valid MBA/BBA degrees or conduct such courses in the state of Uttarakhand. All the articles that appeared in Careers360 were, however yet to appear when the criminal complaint over the 2008 Outlook article was filed (at which time Peri’s team’s investigations into the activities of IIPM were ongoing).

Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code, which is its defamation provision, states that:

- Defamation. – Whoever by words either spoken or intended to be read, or by signs or by visible representations, makes or publishes any imputation concerning any person intending to harm, or knowing or having reason to believe that such imputation will harm, the reputation of such person, is said, except in the cases hereinafter excepted, to defame that person.

Among the exceptions included is the following:

It is not defamation to impute anything which is true concerning any person, if it be for the public good that the imputation should be made or published. Whether or not it is for the public good is a question of fact.

If Peri was to to draw on truth as a defence against the defamation complaint, he thus had to show that his writing was in the public interest. But shouldn’t truth be a defense against defamation in all cases, with due regard to privacy of individuals? This would, of course, require a clear enough definition of privacy, as a vague definition of the same can again be problematic. Is it, for example, ‘in the public interest’ to discuss sexual misconduct by a public official? Does it constitute a breach of privacy? The Abhishek Manu Singhvi case brings out this debate well. Singhvi, a member of the Parliament and lawyer, was caught in a sexual act on camera, inside his chamber, allegedly by his chauffeur. Electronic media were barred from airing the contents of the sex tape through a court order.45 Singhvi’s case is a classic example of two competing issues: public interest and privacy. It can be understood why an injunction against circulation of the video may be granted in a case like this, still leaving open to debate the question of whether the sexual act amounted, in any way, to misuse of public office. However, in cases where public interest and privacy are not dialectically related, truth should be an absolute defense against defamation, whether or not the disclosures are in the public interest.

A magisterial court issued, in March 2009, an ex parte order restraining Outlook magazine from publishing any defamatory articles against IIPM. However, Outlook and Peri got the ex parte order modified by the Delhi High Court to read, among other things, that the magazine could continue to publish articles against IIPM as long as IIPM’s response/rebuttal, if received within two days, would be published with the same prominence in subsequent issues of the magazine without modification.46

The series of articles mentioned before and published later in Careers360 magazine would turn out to provide additional judicial headaches for Peri, as they led to four more defamation cases against Peri and Careers360 in four different places, all by IIPM: in Kamrup, Assam (with Google and Wikipedia among the other defendants);47 in Gurgaon; in Delhi; and in Uttarakhand. The Gurgaon case has in the meantime been stayed by the Chandigarh High Court. In the Uttarakhand case, which involved a criminal complaint, non-bailable warrants against Peri were issued. On 8 October, 2010, the case was quashed by the Uttarakhand High Court in what Peri describes as an ‘exciting judgment.’48 He says that it was the first time that they had been fully heard.

In a clear illustration of the chilling effect of having to appear in courts thousands of kilometers away from where one is based, Maheshwar Peri noted in a telephonic conversation on 22 November, 2012, that because of the various difficulties of dealing with lawsuits in places as remote and unfamiliar as Kamrup judiciary, the businesses he is part of now try to avoid having their articles appear in Assam.

The judicial process had, however, provided Peri with hope as well, as the judgement in the Uttarakhand case noted explicitly that IIPM should have been asked to prove the libelous accusations wrong the very first time the case was heard. In other words, the judge argued that if the charges leveled are indeed true, then defamation cases should not be admissible. It is worthwhile to quote the observations made by the Court at some length here:

The entire edifice of our justice system rests on the principle of truth! … A truth spoken for public good can never be called defamatory. When the author of the disputed article stated in the article itself, in no ambiguous terms, that what he has stated is true and has been verified from Buckingham University and the Berkeley University that they have no arrangements with IIPM, then the first question the learned Magistrate should have asked the complainant was – ‘Do you have the authority to grant this degree from Buckingham University? If yes, show the proof? … But no such evidence was shown, even to this Court! … Yet IIPM in its bold advertisements published in Education Times … states as follows: … MBA & BBA Degree FROM Buckingham Business School, The University of Buckingham, UK.’

Interestingly, in his judgement, the judge seemed to go even beyond what the third exception to section 499 provides for, as he added explicitly:

The emphasis on ‘truth’ by this Court is not a reference on the exception to Section 499, but generally as a matter of caution, must be examined by the Court before issuing summons.

The court also referred to a Supreme Court judgment which clearly lays down that the judicial process cannot be misused for harassing someone. It noted that if the trial court finds that the chances of conviction are bleak, it should not allow criminal proceedings to continue, even at the preliminary stage.

But the court’s recommendation does not seem to have been followed in a more recent case. In 2011, IIPM filed a Rs. 500 million defamation suit against The Caravan magazine, its proprietors Delhi Press, author Siddhartha Deb, the publishing house Penguin Books India and Google India, over an article titled ‘Smell of Success: How Arindam Chaudhuri Made a Fortune Off the Aspirations – and Insecurities – of India’s Middle Classes’.49 The article, authored by Siddhartha Deb and still accessible here,50 appeared in The Caravan in February 2011 and was excerpted from his upcoming book which was to be published by Penguin Books, a reputed publishing house. The article is indeed highly critical of Chaudhuri’s businesses but includes statements dismissing the criticism by Chaudhuri himself as well as by his media manager. While the article also touches upon aspects of Chaudhuri’s life that are more personal (his family, his hairstyle, etc.), it does so in a manner that is not derogatory. Nevertheless, IIPM managed to get a restraining order from the court ordering The Caravan to remove the allegedly libelous article. The restraining order has not been lifted for about two years now.

Though this particular case is not a criminal one, it resembles in a number of troubling ways the string of cases that IIPM has filed against its critics – both civil and criminal. First, while the rationale behind suing most of the said parties is clear, this is not the case for Google. Google was sued for ‘publishing, distributing, giving coverage, circulating, blogging the defamatory, libelous and slanderous articles’ through its search engine. Although Google has a mechanism through which it can be requested not to index defamatory or harmful content, all that the Google search engine does, in fact, is index web pages. That the company has been made a party to this defamation case, therefore, was most surprising and sets an unfortunate precedent where questions about intermediary liability are concerned.51

Second, though The Caravan and IIPM both operate out of New Delhi, the lawsuit was filed in the Court of Civil Judge in Silchar, in the remote and relatively inaccessible state of Assam, because the first plaintiff, Kishorendu Gupta, who operates ‘Gupta Electrical Engineers’ in Silchar,52 is based in Assam and claimed to have accessed the article in Assam (IIPM is the second plaintiff named in the suit). According to The Caravan, Gupta works for the IIPM on a commission basis and receives benefits from IIPM per admission.53

Whether third parties apart from legal firms should be allowed to file defamation suits on behalf of the aggrieved is a question that is worth a debate. It also deserves to be noted that the threat of having to go through court proceedings in remote parts of the country is likely to have a particularly chilling effect on freedom of expression in the Internet age, as it especially affects those without the resources to fight such a case, making the existence of defamation laws that simultaneously provide strong protections for the right to freedom of expression even more important. The Caravan, of course, did take up the fight and filed a transfer petition in the Supreme Court on the grounds that except for one party to the suit, Google, all other parties are based in or around Delhi. The magazine, in a release posted on its website, stated that the matter came up for hearing on 8 August, 2011, and that the Supreme Court of India has issued notice to all other parties on its transfer petition and has stayed the proceedings at the civil court in Silchar.54

Advocate Apar Gupta points out the dangers that arise when large sums of money, bordering on the ridiculous, are claimed as damages in defamation suits.55 The courts, while admitting a defamation suit, must examine the basis of such computation. IIPM, for example, sued The Caravan and others for Rs. 500 million for a piece which did not even challenge the claims that IIPM made in its advertisements – unlike, for example, Careers360 magazine, which did deconstruct the claims, as will be discussed. The very threat of getting sued for such disproportionate amounts, Gupta believes, could be problematic for free speech. While IIPM’s behavior may provide strong arguments to decriminalize defamation, this, in itself, thus not necessarily strengthen freedom of expression.

In fact, according to Gupta, the real issue is the time taken in India for cases to be decided by the courts. For example, in the Khushwant Singh vs Maneka Gandhi case,56 an interim restraining order on the former’s book remained in place for six years, before being removed.57 In order to prevent abuse of the law, Gupta opines, the entire judicial process (including appeals) should be free from unreasonable delays. Clearly, especially in the light of some of the new challenges that the Internet age has thrown up, judicial reform might be necessary and welcomed.

And as mentioned earlier, IIPM has a history of dragging critics to court. In 2005, Rashmi Bansal, who edits a career magazine named JAM (Just Another Magazine), published a story (online58 and in print) deconstructing many of the claims made by IIPM in its brochures and advertisements. The story revealed that IIPM had not been accredited by any Indian accreditation agency such as the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), the University Grants Commission (UGC) or under states’ acts. Bansal received a legal notice from IIPM asking her to remove the ‘defamatory’ content. When she refused to comply, IIPM managed to get an ex parte injunction from the court forcing her to remove the article from her website, meaning that the article is no longer present at the web address referenced to above. In addition to this, IIPM also filed a case against her in a Silchar court. Again, as in the earlier discussed case, the decision to sue in Assam is widely seen as a harassment tactic, given the fact that IIPM is based in New Delhi and JAM in Mumbai. IIPM also filed for damages.

IIPM has also been known to use extra-legal strategies. In August 2005, Gaurav Sabnis, a popular Indian blogger and then-employee of IBM, linked to Rashmi Bansal’s story about IIPM in his blog and added some of his own comments.59 In this post titled ‘The Fraud That Is IIPM,’ he cautioned prospective students against joining IIPM. He then received a notarised email from the President of IIPM’s legal cell, advising him to either delete all of his posts about IIPM posted anywhere on the Internet and tender an apology, or face a lawsuit amounting to Rs. 125 crore.60 When Sabnis didn’t comply, IIPM subsequently complained to a Senior IBM Executive about his company’s employee’s blog posts that were critical of IIPM, leading Sabnis to explain to his Senior that this was his personal blog and that IBM was in no way responsible for what he posted online in his personal capacity. However, in a subsequent email, the Dean of IIPM is understood to have communicated to the Senior Executive a decision by the IIPM Students’ Union to ‘burn Thinkpads’ (laptops) that the institution had purchased from IBM in front of IBM’s Delhi office if Sabnis would not delete his posts. In a clear example of the far-reaching consequences that standing up for your right to freedom of expression can have, although Gaurav was not dooced over the controversy, he chose to quit his job at IBM so that the firm would not be dragged into any controversy because of his actions.61 Sabnis’s post continues to be accessible on the Net.

In this context, where criminal and civil defamation suits are clearly used to silence critics, it would likely be an important boost to the right to freedom of expression on the Internet in India if in future cases, judges will follow the recommendation made by the Uttarakhand High Court in Peri’s case. For example, can the countless portals that allow users to write reviews of products and/or services on the Internet be called defamatory? Section 499 of the IPC hints that ‘harming business interests’ could amount to defamation without making any exceptions for business practices that can be proven unethical before a court of law:

Explanation 2.-It may amount to defamation to make an imputation concerning a company or an association or collection of persons as such.

Where ‘truth in the public interest’ is the only defence available but not at all clearly defined, such provisions can prove to be highly problematic for citizen journalists who expose the shady practices of various business establishments using only a cell phone camera and an Internet connection and without the protection that media houses enjoy.62 If the defamation provision continues to be used as a bullying tactic in the way illustrated in this section, it will hamper both investigative journalism and the right to freedom of expression more broadly.

Finally, in the face of the misuse and harassment by those with the power and resources to do so that is documented in this chapter and elsewhere, including by filing cases in courts around the country, a strong case for the decriminalization of defamation can arguably be made. While, as pointed out earlier, this may not resolve all problems related to the misuse of the law, keeping the criminal defamation provision on the books is a severe threat to freedom of expression in this context, seeing the severe punishments and potential silencing effect on critical and/or dissenting voices that a criminal offence entails.

Protecting the Government and National Symbols: Aseem Trivedi’s Cases #

Aseem Trivedi is an award-winning Indian political cartoonist, anti-corruption crusader and free speech activist. His website www.cartoonsagainstcorruption.com was taken down in December 2011, following complaints that it contained ‘objectionable’ content. After that, four different cases were filed against him in Maharashtra under various provisions of criminal law including sedition and section 66A of the IT Act. He was arrested in September 2012 and he remained in custody for a week. In a telephonic conversation on 4 February, 2013, Aseem Trivedi’s lawyer, Vijay Hiremath, said that the sedition charges against Trivedi have been dropped. But he continues to face charges under the IT Act and the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act. Trivedi’s contentious cartoons63 include one titled ‘National Emblem’, which shows the four Sarnath lions of King Asoka that sit above the motto ‘Satyameva Jayate’ (truth alone shall triumph) as bloodthirsty wolves underscored with the motto ‘Bhrashtamev Jayate’ (long live corruption); ‘Gang Rape of Mother India’, which shows ‘Mother India,’ wearing a tri-color sari, about to be raped by a character labeled ‘Corruption’; and ‘National Toilet,’ which depicts the Parliament as a toilet seat and ballot paper used for voting as the toilet paper.64

Trouble began when, on 27 December, 2011, Aseem Trivedi received an email from BigRock, the domain name registrar with which his website was registered, saying,

We have received a complaint from Crime Branch, Mumbai against domain name ‘cartoonsagainstcorruption.com’ for displaying objectionable pictures and texts related to flag and emblem of India. Hence we have suspended the domain name and its associated services.65

In September 2012, BigRock posted an official explanation on their blog about the takedown which said, among other things, that the takedown was in accordance with the IT Rules notified in 2011.66 As noted earlier in this paper, the IT Rules make it necessary for intermediaries to take action on content reported by aggrieved parties within thirty six hours, or they risk facing prosecution. Soon after his website was taken down, Aseem Trivedi moved his cartoons to Blogger, which is owned by Google. In case a complaint is sent to Blogger, it would again be mandatory for Google to ‘take action’ or risk facing prosecution.67 It can be argued, however, that the complaint should have been sent to BigRock by the aggrieved directly, rather than by the Crime Branch. While the IT Rules already put a tremendous amount of pressure on intermediaries to take down controversial content, this only increases when the police, inappropriately, start to take up the role of messenger.

Following the takedown, four FIRs were registered against Aseem Trivedi – two in Mumbai’s Bandra-Kurla police station and two through the Beed District Court, also in Maharashtra. It was in one of the cases in the District Court that Trivedi was booked on serious charges such as sedition/treason (section 124A of the IPC) as well as under the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, 1971, and under section 66A of the IT Act (sending messages online that are grossly offensive or have a menacing character). All cases were registered on the basis of his cartoons displayed at an anti-corruption rally in 2011 and on his website (which was taken down earlier). In fact, one of the cases in the Bandra-Kurla police station was against Aseem, India Against Corruption (IAC, an anti-corruption movement of which he was a part) and other IAC members like Anna Hazare, Arvind Kejriwal, Kiran Bedi, and others.

Had these cartoons been published in print alone, possibly only the Prevention of Insults to National Honor Act and section 124A could have been invoked against Trivedi, as section 66A does not have an equivalent in the Indian Penal Code in this particular case. In other words, solely on the basis of the cartoons being published online, an additional offence came into existence.

As described before, both the wording and the use of section 66A have come under sharp criticism. The section says:

66A. Any person who sends, by means of a computer resource or a communication device,—

(a) any information that is grossly offensive or has menacing character; or

(b) any information which he knows to be false, but for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill will, persistently by making use of such computer resource or a communication device,

© any electronic mail or electronic mail message for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience or to deceive or to mislead the addressee or recipient about the origin of such messages,

shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and with fine.

It has been widely argued that section 66A violates Article 19 of the Indian Constitution which allows for ‘reasonable restrictions’ on freedom of expression but only in extreme situations like those where public order, national security, etc. is at stake.68 Section 66A of the IT Act has the effect of curbing such freedoms on the Internet even for content that may be deemed ‘annoying’ or ‘inconvenient’ or ‘offensive,’ with no precise definitions offered for the same – all this at the discretion of police.

Furthermore, how the cartoons amounted to ‘sending offensive/menacing messages’ is worth a debate. Pranesh Prakash of the Centre for Internet and Society is of the opinion that,

The explanation to s.66A© explicitly uses the word ‘transmitted’, which is far broader than ‘send’, and it would be difficult to reconcile them unless ‘send’ can encompass sending to the publishing intermediary like Twitter. Part of the narrowing down of s.66A should definitely focus on making it applicable only to directed communication (as is the case with telephones, and with the UK’s Malicious Communication Act), and not be applicable to publishing.69

At present, however, section 66A still refers not only to one-on-one communication but to almost all online communication, making its scope all-encompassing.

The temptation to apply section 66A seems high because of its notorious ability to criminalise actions which weren’t criminalised under traditional law – for example, speech causing annoyance is illegal only when it appears online. Another reason why it is a tool of choice is that it is cognisable – that is, the police do not require a court-issued warrant to be able to make arrests under this section. Combined with a non-bailable section, using this provision thus makes sure that the accused has to seek bail from a magistrate before being released from jail.

The police are known to have acted with unusual diligence in certain cases involving section 66A, often arresting people for their Twitter and Facebook updates under pressure or influence from various entities. The application of section 66A is a good way of ensuring that the accused are harassed even if not convicted. And the section doesn’t entail penalty for false or frivolous complaints.

Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code deals with ‘sedition’. This section predates Independence and was used by the British colonisers to suppress dissent in the erstwhile occupied Indian subcontinent. The United Kingdom itself abolished the sedition law in 2010. The section in the IPC reads:

124A. Sedition. – Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government established by law in India shall be punished with imprisonment for life, to which fine may be added, or with imprisonment which may extend to three years, to which fine may be added, or with fine.

Explanation 1.-The expression ‘disaffection’ includes disloyalty and all feelings of enmity.

Explanation 2.-Comments expressing disapprobation of the measures of the Government with a view to obtain their alteration by lawful means, without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

Explanation 3.-Comments expressing disapprobation of the administrative or other action of the Government without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

The law, thus, criminalises incitement to enmity for the ‘government’ – not the ‘Union’ of India or the ‘Republic’ of India, but the ‘government’. It is surprising that citizens of a free nation should be expected to display ‘loyalty’ and ‘non-enmity’ for the ‘government’ and not do anything that amounts to the contrary. This leaves open all too easily the door to criminalising legitimate criticism of the government – be it online or offline.

The threat to online speech from sedition and other such regressive laws is potentially higher than for offline content, as online content is accessible over a longer time. The ability to take screenshots and, thus, provide ‘proof’ of commission of an offence allows anyone who has enough to gain from the prosecution of someone else’s speech/expression to easily initiate criminal proceedings. One of the complaints which led to Trivedi’s arrest was filed by a member of the Republican Party of India.70 The complaint on which his website was taken down was filed by a member of the Congress party, RP Pandey.71 Trivedi frequently mocked Congress politicians in his cartoons. The possibility that both these complainants had political mileage to derive out of such prosecution is not far-fetched. Indeed, the nature of two of the sections invoked – the Prevention of Insults to National Honor Act and the sedition provision in the IPC – seems to point to an attempt at political and moral grandstanding. This is not to say that the government (in which the Congress party is an ally and of which one of the complainants is a member) had an active role to play in Trivedi’s arrest. But the possibility that the motivation for filing the complaint was political (rather than hurt national sentiment) cannot be dismissed too summarily either – especially as public opinion, in the wake of widespread protests over the issue of corruption, was actually hugely in Trivedi’s favour, in particular after his arrest.72

Following the arrest, the Bombay High Court strongly reprimanded the police and Maharashtra state government for arresting citizens on frivolous grounds and curbing civil liberties.73 The Bombay High Court was hearing a public interest litigation filed by a lawyer Sanskar Marathe against the arrest of Trivedi for sedition. The bench observed that arrests such as Trivedi’s pose a serious threat to freedom of expression and that arrests on such frivolous grounds are unacceptable. The bench also observed that it is important to lay down certain parameters for the application of the sedition law. The court asked, ‘What is the government’s stand now? Does it intend to drop the charge? Someone has to take political responsibility for this.’

The government’s counsel, Advocate General Darius Khambata told the court, ‘After having a close look at the case, it can be seen that there is clearly no case under section 124(a) of IPC for sedition. Hence the government has decided to drop invocation of the charge against Trivedi’ He added, ‘Three cartoons we still find are violative of the National Honour Act and Information Technology Act. Proceedings in this will continue against him.’74 Khambata also described police action against the cartoonist as a ‘bonafide knee jerk reaction’ to the numerous complaints received by the police against the cartoons.

The court again asked the Maharashtra government to clarify its stand on the scope of section 124A by 19 October. On 19 October, 2012, the Maharashtra government filed a draft circular in the court which simply reiterated the exceptions mentioned above: ‘Criticism/disapproval of government with a view to changing it is not seditious.’ The government, however, maintained that the provision is important and that it comes in handy at times.75

Exceptions listed as ‘Explanation 2’ and ‘Explanation 3’ (see description of section 124A earlier) should indeed have been taken into account in this particular case, as the Maharashtra government also maintained. Notwithstanding the exceptions, however, the section itself should be scrapped because it criminalises ‘disaffection’ for the government, even when read along with the exceptions.

Finally, the Prevention of Insults of National Honour Act, 1971 states that:

Whoever in any public place or in any other place within public view burns, mutilates, defaces, defiles, disfigures, destroys, tramples upon or otherwise shows disrespect to or brings into contempt (whether by words, either spoken or written, or by acts) the Indian National Flag or the Constitution of India or any part thereof, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both.

Explanation 1 – Comments expressing disapprobation or criticism of the Constitution or of the Indian National Flag or of any measures of the Government with a view to obtain an amendment of the Constitution of India or an alteration of the Indian National Flag by lawful means do not constitute an offence under this section.76

For the sake of brevity, other explanations under this Act haven’t been listed here. In India, any depiction of national symbols that seeks to denigrate these, or creates such impression, is not only illegal but is also a very sensitive issue. India has a culture of reverence towards national symbols and advocating that the law be scrapped altogether might not be a wise argument. In Trivedi’s case, however, it is debatable whether people actually took offense to such representation or whether it was an attempt by members of political parties to appropriate a law made to prevent insult to national symbols in order to manufacture outrage over the cartoons and thus reap political gain.

Summonses were served at Aseem Trivedi’s home in Kanpur, in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, in his absence. In August 2012, a non-bailable warrant was issued in his name and served to his Kanpur residence where he wasn’t present. In September 2012, Aseem traveled to Mumbai to inquire about the charges against him. He was arrested and remanded to judicial custody for two weeks after he refused bail and asked for the sedition charges against him to be dropped.77 After he was released, he vowed to fight for the abolition of the sedition provision, which is a draconian, colonial law used by the British government to suppress dissent.

Intermediary Liability as well as Hate Speech Provisions Take 1: Vinay Rai’s Case #

Vinay Rai is a Delhi based law graduate and journalist with an experience of 12 years and is currently editing a Noida based Urdu weekly, Akbari. In December 2011, Rai filed a complaint alleging criminal negligence by twenty one Internet companies – including Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Microsoft, Exbii, Shyni Blog, Orkut, YouTube and Blogspot – as they had hosted ‘objectionable content’ on their websites which ‘could lead to riots.’78 Rai filed the FIR under section 109, IPC (‘punishment of abetment if the act abetted is committed in consequence, and where no express provision is made for its punishment’ – this section is used for the prevention of corruption); section 120B, IPC (‘punishment for criminal conspiracy’); section 153A, IPC (‘promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc., and doing acts prejudicial to maintenance of harmony’); section 153B, IPC (‘imputations, assertions prejudicial to national integration’); section 292, IPC (‘sale, etc., of obscene books, etc.’); section 293, IPC (‘sale, etc., of obscene objects to young person’); section 295A, IPC (‘deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings or any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs’); section 298, IPC (‘uttering, words, etc., with deliberate intent to wound the religious feelings of any person’); and section 500, IPC (‘punishment for defamation’).

Both the Indian subsidiaries of these companies as well as the parent companies were initially made parties to the case. While the local divisions of Yahoo and Microsoft were dropped from the case in March 2012, their parent companies continue to face charges.

While Vinay Rai filed the criminal complaint on 16 December, another person named Mufti Aijaz Ashraf Qasmi filed a similar but civil lawsuit against various intermediaries, again for content that could spark riots, later that month. According to a report in Firstpost, Rai and Qasmi have been friends for years.79 Acting upon Qasmi’s complaint, a Delhi court ordered various intermediaries to remove damaging content from their websites.80

The Vinay Rai case, which we will focus on in this section, raised many unanswered questions about two different issues: one, questions surrounding intermediary liability and procedural loopholes in the law, and two, the challenge that laws to protect community sensitivities pose to freedom of expression in the Internet age.

Let us look at the issue of intermediary liability first. In a report submitted to the trial court, the Ministry of Information Technology said that the government of India is satisfied that the content complained about violates the IT Rules notified in 2011.81 Rule (4) of the IT Rules reads:

The intermediary, on whose computer system the information is stored or hosted or published, upon obtaining knowledge by itself or been brought to actual knowledge by an affected person in writing or through email signed with electronic signature about any such information as mentioned in sub-rule (2) above, shall act within thirty six hours and where applicable, work with user or owner of such information to disable such information that is in contravention of sub-rule (2) (emphasis ours).

Thus, unless the intermediary has ‘obtained knowledge by itself’ of infringing content or has been ‘brought to actual knowledge by an affected person in writing or through email signed with electronic signature’ of such content, the intermediaries are protected from prosecution under section 79 of the IT Act, also known as the ‘safe harbour’ provision.

It is clear that the IT Rules were never invoked by the complainant, as no formal representation for content removal was made to any of the intermediaries. In fact, in an interview to the Wall Street Journal, Vinay Rai admitted that he did not follow this prescribed path as he did not want to complain to ‘foreign companies’, and that he decided to make a representation before the government instead. Rai disclosed in the Wall Street Journal interview that he had been in talks with the government for about a year before filing a criminal complaint in December 2011.82 Interestingly, the Minister of Information Technology, Mr. Kapil Sibal had been meeting the companies since August 2011, asking them to remove and even ‘prescreen’ certain content, even before it’s uploaded. Sibal had shown examples of objectionable content to the intermediaries in these meetings, including a derogatory Facebook post about Sonia Gandhi, President of the ruling Congress Party.83 In a telephonic conversation on 29 March, 2013, Rai denied having complained himself about content that was political in nature. He said that he had only brought to the attention of the government blasphemous content that could hurt the sentiments of people belonging to various communities. However, Rai complained, the Ministry did not respond promptly. In his criminal complaint, Rai claimed that he was now bringing the issue to the notice of the judiciary not only in the public interest but as a person who believes in a secular India as well.

It is clear that the presiding judge did find some of the content that he was shown deeply troubling. On 23 December, 2011, the Patiala House Court issued summons to Indian heads of various companies in the case and also asked the Ministry of External Affairs to have summons served to Chief Executives of various intermediaries which are headquartered abroad, including Steve Ballmer of Microsoft and Larry Page of Google. In the summons, Justice Sudesh Kumar also commented that the government of India had in fact ‘turned a blind eye towards the offensive, degrading and demeaning content on these websites which is outrageous and also against national integration’ and asked it to file a report regarding the same on the next hearing, i.e. 13 January, 2012. The court noted that the accused persons are liable to be summoned for offences under sections 153A, 153B and 295A of the IPC, all sections that protect the sensitivities of and the relations among different communities.

Under section 196 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), a court cannot take cognisance of a case under section 295A, however, without the previous sanction of the Central Government or State Government or District Magistrate. On 13 January, 2012, the Government of India’s Department of Telecom submitted its report through its counsel, Seema Sharma, in the trial court, saying:

Government of India after being satisfied that such contents are violative [sic] of the provisions of the information technology (intermediaries and guidelines) rules 2001 [sic] and after due application of judicious minds find it appropriate to grant sanction under 196 of CrPC to proceed against the accused persons in the aforesaid complaint in national harmony, integration and national interest

thus granting permission to the trial court to proceed.84

In the meantime, various intermediaries had approached the Delhi High Court through their counsels to have the summons quashed, but the same was denied to them. Also on 13 January, 2012, the Delhi High Court upheld the summons issued by the trial court and gave permission for prosecution.85 What caused particular alarm at that time was the remark by Justice Kait of the Delhi High Court, ‘You just have a stringent check. Otherwise, like China, we may pass orders banning all such web sites.’86 Justice Kait made this remark while responding to the plea by an intermediary stating, ‘No human interference is possible, and moreover, it can’t be feasible to check such incidents. Billions of people across the globe post their articles on the website.’ That an Indian court should make a remark which, in effect, makes China the benchmark of freedom and democracy, is rather upsetting, for the Indian judiciary is supposed to be the guardian of democracy.

Before the next hearing – which was to take place on 13 March, 2012, in the trial court – Google and Facebook, in the course of questioning the proceedings, argued before the Delhi High Court that the complaint by Vinay Rai, upon which the case was based, should be considered a private complaint and that the Government of India should not be made a party to it. The High Court, however, struck down the plea, maintaining that:

This cannot be treated as a private complaint. It is not a complaint where only the complainant is the victim and nobody else is affected. It is a complaint wherein the complainant has alleged that the websites published objectionable materials against some great national personalities and religious figures.87

Justice Suresh Kait added that the assistance of the Delhi Police and the Centre was sought because the trial court had called for a report from the Centre for assistance in the case. Thus, on 14 February, 2012, the Government of India became a party to the case.

The addition of the government to the parties in the case ads an additional complication. As section 79 of the IT Act mentions this as an additional condition under which intermediaries can lose the safe harbour protection, could it perhaps be argued now that the intermediaries had been ‘notified by the appropriate Government or its agency’ that unlawful content was being hosted on its platforms? As we do not have access to the communication between the government and the intermediaries, it is difficult to comment on this matter in a conclusive manner. But some observations can be made. Seeing that these were supposed to remain a secret, it would be disconcerting if the meetings held by the government with the heads of certain companies in 2011 would be considered a formal notification ‘by the Government or its appropriate agency,’ as the government’s counsel seems to maintain.88 As with the complaints of private persons, it is crucial for the sake of accountability that any complaints or notifications can be traced through a paper or electronic trail. Even if the meetings were to qualify as formal complaints, among the accused, only Google, Yahoo, Microsoft and Facebook were part of these meetings. Were all the accused in this case asked to remove inflammatory content before being taken to court? If not, then it could well be argued that the criminal proceedings against them are in violation of the safe harbor provision under section 79 of the IT Act – unless the Government had intimated all of the accused about its concerns in any other way. As noted before, without additional information about the communication, this is not something that we can conclusively comment on.

At the time of writing, the next hearing of the Vinay Rai vs. Intermediaries case is scheduled for December 4, 2013, in the Patiala House Court. For those concerned with the freedom of expression on the Internet in India, it remains important to follow this case closely, as strong safe harbour provisions for intermediaries are not only crucial for intermediaries themselves, but for all of us, as they are central to our ability to speak freely online. That Rai’s complaint was accepted by the Court despite the fact that Rai had not followed established procedure had caused sincere alarm among those concerned with freedom of expression on the Internet in India. It is hoped that the outcome of the case will prove that this alarm was ultimately unfounded.

Questions around intermediary liability are not, however, the only ones thrown up by the Vinay Rai case. Though an angle that has been less explored so far, it also brings into focus the challenge that laws that protect the sensitivities of and relationships among India’s many different communities pose at times. Sections 153A, 295A and 505(2) of the IPC, some of which were mentioned by Justice Sudesh Kumar in his summonses to the Indian heads of various intermediaries, are of particular importance here. They read as follows:

153A. Promoting enmity between different groups on ground of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc., and doing acts prejudicial to maintenance of harmony. – (1) Whoever-

(a) by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise, promotes or attempts to promote, on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community or any other ground whatsoever, disharmony or feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will between different religious, racials, language or regional groups or castes or communities

shall be punished with imprisonment which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both.

505(2) Statements creating or promoting enmity, hatred or ill-will between classes. – Whoever makes, publishes or circulates any statement or report containing rumour or alarming news with intent to create or promote, or which is likely to create or promote, on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community or any other ground whatsoever, feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will between different religious, racial, language or regional groups or castes or communities, shall be punished with imprisonment which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both.

295A. Deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs. – Whoever, with deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any class of citizens of India by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise insults or attempts to insult the religion or the religious beliefs of that class, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both.

That India has provisions on its books that aim to ensure the peaceful coexistence of its many communities is, seeing its size and diversity, understandable. But the ways in which the provisions have been phrased might ultimately have done more harm than good to freedom of expression, as well as to the peaceful coexistence of India’s communities in fact. Indeed, these provisions have allowed reference to a group identity, in combination with the orchestration of an actual or potential threat of group violence, to emerge as effective means for groups to impose their worldview on others, including through what appear as ever-widening restrictions on freedom of expression. In other words, it is those who are most willing to revert to violence if need be who de facto become the ‘custodians’ of the ‘community’s identity’, while those with alternative visions who do not support such aggressive strategies are effectively marginalised.89 As the potential of the Internet to give voice to the hitherto voiceless largely remains, this tension will likely be felt only more and more acutely as an ever larger number of Indians comes online, voicing opinions and beliefs that have for long, at least publicly, remained largely unsaid and with that, possibly challenging the self-representations and self-understandings of others. If those who do not want to resort to aggression are to continue to find their voice online, the laws that seek to manage the relationships between India’s communities will need to change.

More specifically, as this borders on a blasphemy law, section 295A, which prohibits insults to religious beliefs, should be scrapped. While believers of all religious communities, as well as those who do not adhere to any religion, should indeed be protected, religious beliefs as such should not. Without the right to question, be it one’s own religion or another, the right to religion becomes meaningless. Those who engage in violence because their own beliefs are questioned or challenged should not be protected by the law on that account.

Sections 153A and 505(2), which could be considered India’s primary hate speech provisions, would benefit from modifications. In particular, to be effective yet supportive of the right to freedom of expression, they require a clear delineation of thresholds which are set high, including an implicit or explicit acknowledgment of the power relations between communities. Unless hate speech provisions include recognition of structural and historical discrimination, their implementation will likely continue to disproportionately benefit those who already are in a more powerful position than their adversaries, however relative that position might be. The next case that we will discuss in this paper, that of Shaheen Dhada, makes this amply clear.

Hate Speech Provisions Take II: Shaheen Dhada’s Case #

On 17 November, 2012, Bal Thackeray, the founder of the Shiv Sena, a right-wing ethnocentric party, passed away in Mumbai, the Shiv Sena’s stronghold. This was preceded by a brief illness and anticipation of Bal Thackeray’s (then impending) death. The supporters of the political outfit have a history of attacking business establishments, public property, etc. and there were widespread apprehensions that his funeral will be marked by violence.90 News of his death, thus, brought Mumbai to a standstill for the weekend, with businesses shutting and taxis going off the roads, amid fears of violence by Thackeray’s supporters.91

On 19 November, 2012, news surfaced of the arrest of two girls from Palghar district, on the outskirts of Mumbai, for having questioned the bandh (shutdown) on Facebook. In a Facebook post, Dhada had written,

With all respect, every day, thousands of people die, but still the world moves on. Just due to one politician died a natural death, everyone just goes bonkers. They should know, we are resilient by force, not by choice. When was the last time, did anyone showed some respect or even a two-minute silence for Shaheed Bhagat Singh, Azad, Sukhdev or any of the people because of whom we are free-living Indians? Respect is earned, given, and definitely not forced. Today, Mumbai shuts down due to fear, not due to respect.92

The complaint was filed by Palghar Shiv Sena chief Bhushan Anant Sankhe.93 Dhada’s friend Rinu Srinivasan, who had liked, shared and commented on the post on Facebook was also arrested. Her comment read: ‘Everyone know it’s done because of fear!!! We agree that he has done a lot of good things. also we respect him, it doesn’t make sense to shut down everything! Respect can be shown in many other ways!’94 She later deleted the shared post from her timeline and also removed her comment, after a friend warned her.

The FIR was filed under section 295A of the IPC (‘deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs’) and section 66A of the IT Act (‘sending messages that are grossly offensive or menacing in character through electronic medium’).95 As explained earlier, section 66A is cognisable; therefore the police can arrest a person without a warrant. On the night of 20 November, 2012, just hours after the status update, the two girls were summoned by the Palghar police, detained overnight and arrested in the morning. Before this, members of the Shiv Sena had ransacked the clinic belonging to Dhada’s uncle and harassed the patients therein. Police action in this case was highly unacceptable even though it may have been under pressure from Shiv Sena activists. The application of section 66A was clearly unjustified, as posting a political opinion on Facebook in a perfectly civil manner is legitimate speech, which must not be criminalised.

The application to this case of section 295A, which comes close to a ‘blasphemy’ law, soon turned out to be controversial, however. For prosecution under section 295A, it is required to demonstrate malicious and deliberate intent to outrage religious feelings. In this case, however, no reference to any religious belief or religion was made in the first place: the comments may have upset Thackeray’s followers but they were by no means disrespectful to any religion or religious belief as Thackeray was a political leader.